The Nigerian uranium grab story dates back to the pre-independence era, during the post-war period when the Gaullist government - and later the Fourth Republic- decided to establish a nuclear industry in France. On the civilian side, a five-year nuclear energy development plan was launched in 1952, leading to the inauguration of the first experimental reactor at Marcoule, in the Gard region of France, four years later, and the launch of the first power plant in 1963. On the military side, Paris secretly committed itself to developing a deterrent force and detonated its first atomic bomb in the Algerian desert in February 1960.

Uranium supplies still had to follow. The deposits at Lachaux, in the Puy-de-Dôme region, Saint-Sylvestre, Limousin region, and Grury, Morvan region, can meet immediate needs. However, production in mainland France will not be able to meet the growing demand from the industry. So prospectors from the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique (CEA), created in October 1945, set out to survey the empire1, from Morocco to Cameroon, from the Ivory Coast to Oubangui-Chari (today’s Central African Republic), through Madagascar, Dahomey (today’s Benin) and Sudan (today’s Mali). Hopes were pinned on the Boko Songo site in Congo (Brazzaville) and deposits in Madagascar, but industrial mining projects were eventually abandoned2.

In 1956, prospecting efforts were finally rewarded with the discovery of Gabon’s Mounana deposit, “a wonderful truffle of 5,000 tonnes of uranium”, in the words of Jacques Blanc3, Cogema’s General Secretary in the 1970s-1980s4. Two years later, signs of uranium were discovered by the Bureau de Recherche géologique et minière (BRGM) in Niger, in the Azelik region, during a search for copper deposits. In January 1959, the CEA obtained a prospecting authorization, and in July, a first exploration permit covering an area of 50,000 km² on the plains and plateaus bordering the Aïr massif: the Talak plain in the west, the Agadez plain in the south, and the Toguedi and Tégama plateaus further south.

Almost exclusive control

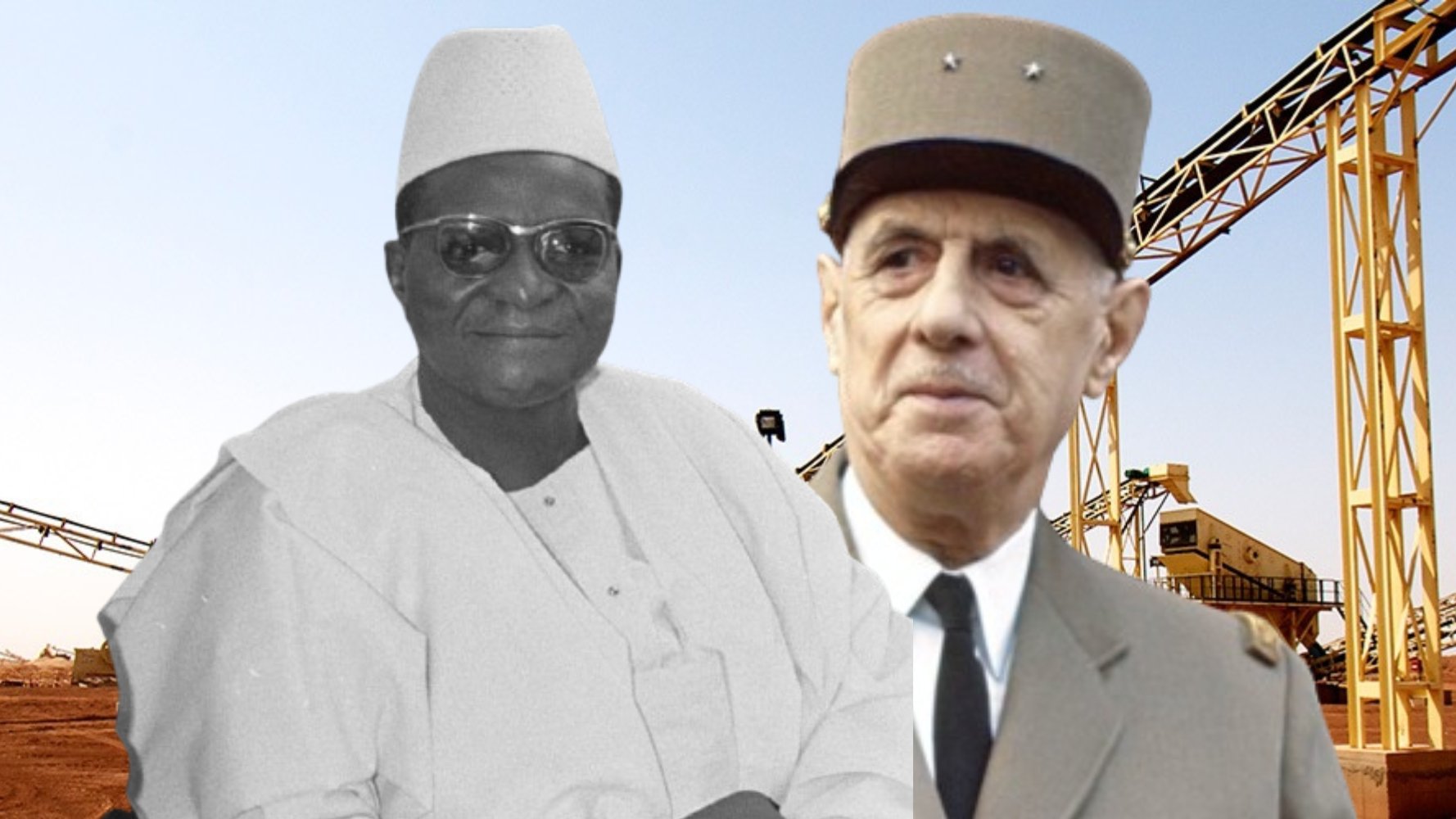

But the political situation in Niger was tense. The trade unionist Djibo Bakary, head of the Sawaba movement, was elected mayor of Niamey in October 1956, then president of Niger’s first autonomous government. A supporter of immediate independence, he (like Sékou Touré in Guinea) voted “no” to the creation of a “French Community” in the September 1958 referendum. The colonial administration sabotaged the electoral campaign, increasing pressure and stuffing the ballot boxes to ensure a “yes” victory. Following what researcher Klaas van Walraven describes as “Africa’s first modern coup d’État”, Djibo Bakary resigned and his party was dissolved, forcing him into hiding and refuge in Ghana5. A supporter of the French Community, the very Francophile Hamani Diori, replaced him as head of government and, in August 1960, became the first president of independent Niger. Paris finally had a conciliatory interlocutor to secure its access to strategic raw materials, foremost among them uranium.

As in other parts of Africa, Niger’s independence was contingent on a series of agreements that connected the new state to the former colonial power. These agreements have a military dimension, which is the best known, but they also cover a wide range of areas, including raw materials. The annex to the defense agreement between the governments of the French Republic, the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire, the Republic of Dahomey, and the Republic of Niger of April 24, 1961 (download below) considers “uranium, thorium, lithium, beryllium [and] their ores and compounds” to be “raw materials and products classified as strategic”. As a result, the signatory countries “reserve priority for their sale to the French Republic after satisfying their domestic consumption needs”. And “when defense interests so require, [they] limit or prohibit their export to other countries”. In other words, France assumed almost exclusive control over future uranium production in the New Independent States...

Backed by these guarantees, aerial prospecting campaigns and drilling in the Niger desert accelerated. New research permits and prospecting authorizations extended the field of investigation eastwards (1962) and southwards (1963), right up to the Nigerian border. From 1965 onwards, CEA’s efforts focused on the Arlit region, where the results were most encouraging, and then more precisely on a few square kilometers in the “Arlette” zone, which recorded the highest grades. Semi-industrial processing trials were carried out. They demonstrate the deposit’s exploitable potential.

A highly beneficial agreement for Paris

Negotiations soon got underway. In an exchange of letters dated January 25, 1967 (download below), President Hamani Diori confirmed to French Foreign Minister Maurice Couve de Murville - who was to become Prime Minister a few months later - that “Niger is determined to facilitate the development of the deposits for which the exploitation rights have already been granted to France”. The French minister, for his part, declared his readiness to “begin construction of the facilities necessary for exploitation by the end of 1967”, and proposed sending a mission of experts to rapidly conclude “a formal agreement guaranteeing the interests of both parties”, naturally “in the spirit of the Franco-Nigerian agreements” of 1961.

On July 6, 1967, the President of Niger met General Charles de Gaulle in Paris to finalize the negotiations. The “Protocole relatif à la création d’une mine d’uranium au Niger” (download below) was signed the next day by Hamani Diori and the CEA. It stipulated that the “Arlette” deposit would be exploited by a company domiciled in Niger, Société des Mines de l’Aïr (Somaïr), created for the occasion and controlled 45 % by the CEA, 40 % by private French interests and 15 % by the State of Niger.

The CEA’s contribution in kind - its mining titles and “studies, plans and work carried out by itself [on the zone] before January 1, 1967” - is valued at 500 million CFA francs or half of its capital contribution. In return for this contribution in kind, the CEA will receive a royalty of “2 % of the ex-works value of concentrates shipped” over the first 500 tonnes. The agreement also provides for an increase in this royalty to reimburse the CEA for any investments it may make in road access to the Arlit region, which it needs to evacuate the ore. Above all, and perhaps most importantly for Paris, the CEA, which undertakes to purchase at least 1,000 tonnes of uranium each year “at a normal price by reference to the world market for comparable transactions”, “will have priority of purchase over the Company’s production”. The supply of French nuclear power is granted!

Tailor-made for the CEA

The 1967 agreement was the cornerstone of the legal framework that would govern uranium mining in Niger for many years to come. In a letter to Robert Schuman (download below), then Minister of State for Scientific Research and Atomic and Space Issues, Hamani Diori undertook to adopt a tailor-made fiscal regime for uranium, “adapted to the foreseeable conditions of extraction and processing of this mineral in Niger” - which he did in January 1968.

On January 17, 1968, a decree granted the CEA mining rights over 360 km² (download below) in the department of Agadez - the “Arlit concession” - for a period of... 75 years6 !

The agreement appended to this concession guarantees the CEA the application of any more favorable provisions from which a competitor might benefit, throughout these 75 years. The CEA, and consequently Somaïr, to whom the operation will be entrusted8, naturally have “free use of the land and installations of all kinds used for the operation», including «water wells, airfields, work camps” and “waste rock dumps”7. In the event of a dispute, the agreement provides for recourse to a private arbitration court.

On February 2, 1968, Somaïr signed a “long-term settlement agreement” (download below) with the Nigerien government, highlighting the conditions under which the deposit would be exploited. The company undertook the necessary investments to increase annual uranium production to 200 tonnes in 1970 and to 1,000 tonnes in 19738.

Somaïr must build the capacities of the Nigerien workforce it employs and house them “in normal health and safety conditions”, respect freedom of association, help set up a medical and educational infrastructure, and contribute to the organization of leisure activities for its workers. For its part, Niger guarantees fiscal stability - particularly advantageous in terms of investment depreciation conditions and tax exemptions - the free repatriation of capital and the free export of uranium for the entire duration of the agreement, i.e. twenty years from the date of the first commercial shipment. Any legislative or regulatory changes in these areas can only be applied to Somaïr if they are more favorable. On the other hand, nothing, not a single line, is devoted to the prevention of the specific risks of uranium for workers or to the environmental conditions of the operation, apart from the authorization to use, without restriction, underground water for production needs.

A straitjacket destined to last

With this body of legislation, the framework for uranium mining was set for the long term9. The mining concession granted to the CEA in 1968 runs until 2043, a fact that Cogema, then Areva, and then Orano - Somaïr’s successive French shareholders - are quick to point out at every negotiation.

The purchase of uranium “at a normal price by reference to the world market for comparable transactions”, the famous “Niger price” (see next episode), gave rise to numerous tussles between Niger and the French company : as early as 1974 with President Hamani Diori, in 2007-2008 with Mamadou Tandja and again in 2014 with Mahamadou Issoufou. Above all, Somaïr’s convention d’établissement, extended twice10, will govern the company’s activities until a new agreement (download below) comes into force on January 1, 2004. That’s 33 years of unrestricted exploitation of Niger’s uranium...

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism :

1A decree of April 1946 reserves for the State the rights to research and exploit radioactive substances in all territories under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Overseas, with the exception of the French West Indies and Reunion Island.

2Robert Edgard Ndong, “La recherche de l’uranium en Afrique française et la naissance de la Compagnie des mines d’uranium de Franceville (COMUF), 1946-1958”, Outre-mers, 99-374/375, 2012.

3Jacques Blanc, “Les mines d’uranium et leurs mineurs français : une belle aventure”, Annales des mines - Réalités industrielles, La France et les mines d’Outremer dans les trente glorieuses, 2008.

4Compagnie Générale des Matières Nucléaires (Cogema), the forerunner of Areva and Orano, was created in 1976 to take over all the activities of the Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique (CEA)’s “production division”, which was responsible for uranium production in France and Africa. The company, which remained under CEA control, gradually integrated uranium enrichment, trading and reprocessing activities. In June 2001, Cogema merged with Framatome (nuclear power plant design, equipment and maintenance), TechnicAtome (design and production of compact nuclear reactors, in particular for naval propulsion) and CEA Industrie (the CEA’s industrial holding company) to form Topco, an integrated public nuclear group which finally took the commercial name of Areva three months later. In January 2018, following a major restructuring of Areva, the group refocused on the nuclear fuel cycle and became Orano. The multinational is still 90 % owned by the French state.

5Klaas van Walraven, “La portée historique du Sawaba. La France et la destruction d’un mouvement social au Niger, 1958-1974”, Les Temps modernes, 693-694, 2017, p. 174 à 194.

6This concession period, which complies with Niger’s 1961 mining law, is nonetheless exceptionally long. Niger’s mining code of July 2022, for example, provides for a maximum term of 10 years for all mining titles. In accordance with the principle of non-retroactivity of the law, however, the same code specifies that ‘mining titles and concessions valid on the date of entry into force of the present law remain valid for the duration and substances for which they were issued’, i.e. until 2043 for the Arlit concession held by CEA, now Orano.

7Mine ‘waste rock’ is all the material extracted before reaching the ore. This is landfill.

8Production actually began in 1971, a year late, and exceeded 1,000 tonnes in 1974.

9This framework is broadly reproduced in the establishment agreement of July 1974, which sets out the conditions for mining the Akouta deposit for 25 years from the date of first commercial export. This is the second mine - underground this time - in the Arlit agreement, leased by the CEA to the Compagnie minière d’Akouta (Cominak).

10The agreement was extended twice by addenda and ‘by mutual agreement’, first until 31 December 1996 when new tax provisions were introduced in 1974, and then until 31 December 2003, without further amendments, in 1995.