It is the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs itself that says so on its website: “The election of President Alassane Ouattara has opened a new chapter in Franco-Ivorian relations.” Since 2011, Alassane Ouattara, now 83 years old, has become one of the African heads of state closest to France – just as anticipated by those at the Élysée Palace, the Quai d’Orsay, major institutions, and multinational companies who supported his rise to power. Through his political and economic choices, he has consistently served Paris’s interests.

“When one is a friend of France, one must think of French companies,” Nicolas Sarkozy is said to have whispered in Laurent Gbagbo’s ear in 2007 – a few years before toppling him. Alassane Ouattara, for his part, did not need to be reminded of this unwritten rule of Franco-African relations. In January 2012, during a state visit to Paris, he made a pressing appeal to French business leaders: “I invite you to return to Côte d’Ivoire, to invest there massively, and I know you will do so. Côte d’Ivoire needs your talent and expertise.”

Since then, the Ivorian government has done everything possible to attract French multinationals and strengthen their presence – tax incentives, legal security, public-private partnerships, and more. As a result, Côte d’Ivoire today counts more than a thousand French companies operating within its territory, compared to around six hundred, fifteen years ago. Among them are several heavyweights of the economy: Auchan, Carrefour, Decathlon, Orange, and TotalEnergies…

Bouygues and Bolloré first to be served

The Bouygues Group, historically close to Alassane Ouattara since the 1990s, has been particularly favoured, securing several major projects: the construction of a third bridge in Abidjan, inaugurated in 2014; the future metro line of the economic capital; and the rehabilitation and expansion of the international airport. Before the Bolloré Group withdrew from the African logistics sector in 2022, it too had been well rewarded, notably by obtaining the monopoly over port operations in Abidjan.

Several of the most significant contracts won by French companies in Côte d’Ivoire were financed through loans from the French state to the Ivorian state. To seal some of these deals, France’s Minister of the Economy, Bruno Le Maire (in office from 2017 to 2024), personally travelled to Abidjan on two occasions – a level of attention he granted to no other African country. During his second visit, he adopted a paternalistic tone, declaring: “I came to make sure that things are moving forward,” referring to the “major projects we have set up together.” He even addressed the Ivorian president informally, calling him “dear Alassane” and praising his “wisdom.”

For French companies, the profits are certainly there. Orange, for instance, has recorded steady revenue growth in Côte d’Ivoire, which is one of its most dynamic markets in Africa. And the authorities of both countries are eager to maintain this situation. At the end of 2024, a delegation of French companies travelled to Abidjan to explore new opportunities. On that occasion, Côte d’Ivoire’s Minister of Economy, Planning and Development, Nialé Kaba, invited them to continue investing: “Our economy is ready to welcome innovative investments and to support partnerships that are beneficial to both parties.”

Ensuring the CFA franc’s sustainability

Cote d’Ivoire also occupies a strategic position in France’s cooperation programme, as evidenced by the scale of the commitments made by the French Development Agency (AFD), which manages one of its largest portfolios in Africa there. Among its instruments, Debt Reduction and Development Contracts (C2D) plays a central role: this mechanism consists of cancelling Cote d’Ivoire ’s bilateral debt to France and then relocating the corresponding sums to development projects supervised by the AFD.

Since 2012, nearly €3 billion has been reinvested via the C2D in key sectors such as education, health, infrastructure and agriculture. The AFD also finances flagship projects such as the professional integration of young people, which give it direct access to Ivorian public policies. Through, this density of interventions, the logic of influence, economic anchoring and maintenance of an asymmetrical relationship is unfolding.

Over the past few years, Paris has also been able to rely on Alassane Ouattara to ensure the continued existence of the CFA franc, a currency he had already served for a long time before becoming president, notably as Governor of the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO). Still under French tutelage, this monetary arrangement is of great benefit to French companies operating in Cote d’Ivoire, since it allows them to repatriate their profits without constraint.

From 2015 onward, popular mobilisations emerged in several West African countries demanding an end to this dependence and the establishment of monetary sovereignty. Alassane Ouattara emerged as an unshakeable defender of the system.

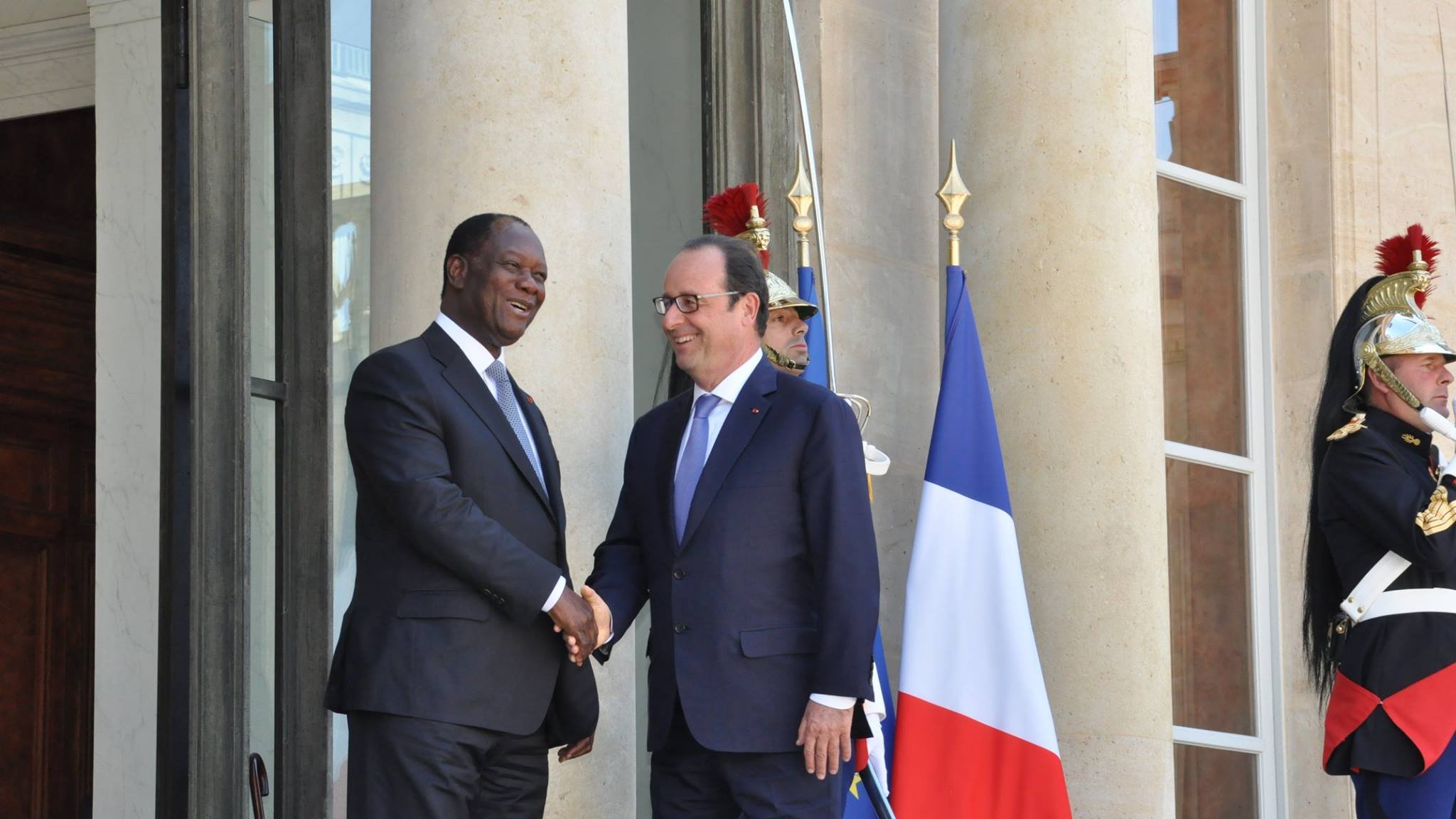

In February 2019, after a meeting at the Elysee Palace with President Emmanuel Macron, he stated, for example “The CFA franc is our currency. It is the currency of the countries that freely agreed to it and have implemented it in a sovereign manner since independence in 1960,” repeating almost word for word the argument put forward by the French authorities, who at the time wrongly presented the CFA franc as an “African currency”.

French army’s last ally

A few months later, in December 2019, Alassane Ouattara willingly served as Emmanuel Macron’s guarantor during the French president’s visit to Abidjan to announce a reform of the West African CFA franc. Presented as a major development, this restructuring was in fact aimed at preserving the core foundations of the existing system while neutralising the rival single-currency project promoted by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

During his three terms in office, Alassane Ouattara has also taken care to preserve France’s strategic interests. It would have been difficult for him to do otherwise: this preservation is largely thanks to France military intervention.

Over the years, President Ouattara has become one of the last steadfast allies of the French military establishment in West Africa, at a time when French troops have been forced to withdraw from several neighbouring countries. Until February, French forces maintained a permanent base in Abidjan, which has since been officially transferred to the Ivorian state as part of the reorganisation of France’s military presence on the continent. When announcing this handover to his fellow citizens, the Ivorian president portrayed it as a major step toward the country’s military sovereignty. Yet behind this rhetoric – meant to address popular aspirations for greater autonomy – the reality is more nuanced. Security cooperation with France remains active: Côte d’Ivoire continues to host several dozen French soldiers and still plays a central role in Paris’s strategic apparatus in the region.

French reconversion

Beyond institutional frameworks, Alassane Ouattara continues to maintain personal ties with key figures in France’s high political and economic circles. In 2018, he welcomed Michel Camdessus, former Managing Director of the IMF, to Abidjan. The two had worked together in the 1990s, and Camdessus had helped Ouattara build a strong political network in France. Three years later, in 2021, the Ivorian president was among the few carefully selected guests invited by the Élysée to a ceremony held in honour of the former senior official.

He also extended a privileged welcome to Nicolas Sarkozy, one of his most loyal supporters since the 1990s and the main architect of the political-military operation that brought him to power. Before his judicial convictions in France, the former president made numerous visits to Côte d’Ivoire. He came for political activities – attending all the inaugurations of his friend (2011, 2015, 2020) – but also for business, notably as an advocate for the interests of the Accor group, which took control of several major hotels, including the famous Hôtel Ivoire in Abidjan. He also made more discreet visits in a private capacity. The relationship remained so close that he is sometimes received privately in Mougins, at the Ouattara couple’s residence on the French Riviera.

Under Ouattara’s era, several former senior French officials, military officers, or ministers, once their missions were completed, also found in Côte d’Ivoire a favourable environment for economic reinvention. Among them is Georges Serre, the former French ambassador to Abidjan (2012–2017), who became Africa advisor for the CMA-CGM group, a global leader in maritime transport. In 2018, he accompanied CEO Rodolphe Saadé on an official visit and organised a reception in Abidjan that brought together more than 200 business figures. He was then provided with a security escort by the Ivorian presidency. His predecessor, Jean-Marc Simon, who served in Abidjan between 2009 and 2012, founded a consulting firm to support companies active in or wishing to establish themselves in Côte d’Ivoire, while remaining very close to Alassane Ouattara.

Dinners “among friends” with the Macrons

Meanwhile Dominique Ouattara, the president’s wife, continues to develop her own network of influence in France, notably through her Children of African foundation. She solicits funds from major French companies and organises an annual gala dinner attended by Nicolas Sarkozy, former ambassadors, powerful business leaders and figures from the French and Ivorian entertainment industry.

Still active in Parisian social circles, Dominique Ouattara regularly appears alongside influential figures. In 2018, she was photographed with Martin and Mélissa Bouygues, Baron David de Rothschild, and the artist Line Renaud at a reception held to celebrate the latter’s 90th birthday. She also receives visits of a more political nature in Abidjan: in 2023, she welcomed two French deputies with whom she discussed, among other things, “the improvement of diplomatic relations between France and Côte d’Ivoire”. Her daughter, Nathalie Folloroux, serves as the programming director of Canal+ International, an influential channel across Africa owned by the Bolloré group.

Within this tight-knit Franco-Ivorian network of alliances, the relationships between heads of state naturally remain central. Alassane Ouattara regularly meets with his counterpart Emmanuel Macron, both in the context of official meetings and in encounters not listed on public agendas. In January 2025, Africa Intelligence reported that he had been “discreetly received for dinner at the Élysée.” Jeune Afrique notes that President Macron and his wife have made a habit of inviting the Ouattaras to “friendly” dinners, during which they notably discuss the political situation in several West African countries where France maintains strategic interests. Ultimately, the ties between Alassane Ouattara and France are so close that Côte d’Ivoire almost appears as an extension of the French state in West Africa.

Random arrests and disproportionate use of force

This unwavering loyalty earns him constant political support and a benevolent tolerance from Paris, even as the authoritarian excesses of his regime are widely documented.

The trend became apparent following the end of the 2010–2011 post-election crisis, which officially claimed more than 3,000 lives. In the transitional justice system set up by the new government, only supporters of Laurent Gbagbo were prosecuted. Abuses committed by pro-Ouattara forces – summary executions, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary arrests – remained largely unpunished. In 2018, an amnesty law, adopted in the name of national reconciliation, extended this impunity to nearly 800 people, including officials involved in serious crimes. Several NGOs, including the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Amnesty International, argued that this measure obstructed justice and the duty of remembrance.

Since then, Alassane Ouattara has governed in an environment marked by regular violations of public freedoms and fundamental rights. Arbitrary arrests of opponents, disproportionate use of force during demonstrations, pressure on the media, and the politicisation of the judiciary – these abuses are regularly reported by NGOs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, yet they are denied by the Ivorian authorities.

When President Ouattara decided in 2020 to run for a third term, in violation of the spirit of the Constitution, which allows only two, repression reached a new peak. Demonstrations were violently dispersed, resulting in more than 80 deaths. Opposition leader Pascal Affi N’Guessan was arrested and held in secret detention. Other political and civil society figures were imprisoned or silenced.

All the boxes of the ideal ally

In 2025, the scenario repeated itself. Just days after a discreet visit to the Élysée, Alassane Ouattara announced his candidacy for a fourth term. The political landscape was then locked down like never before: the main opponents, Laurent Gbagbo and Tidjane Thiam, were barred from the election on widely contested grounds, dozens of activists and party officials were imprisoned, and the voter registry was marred by serious irregularities.

While NGOs express concern– “Authorities must stop repressing peaceful demonstrations ahead of the presidential election,” warned Amnesty International on October 16, 2025 – the French authorities remained remarkably silent. Their restraint stands in sharp contrast to the Gbagbo years: under Jacques Chirac and then Nicolas Sarkozy, Paris frequently issued critical statements regarding the Ivorian president.

In the history books, Alassane Ouattara will most likely be remembered as France’s closest “friend” in West Africa during the 2010s and 2020s. An active defender of the CFA franc, a protector of French economic and military interests, and a reliable diplomatic intermediary, he has checked all the boxes of the ideal ally. He will most likely remain so for some time, as long as he stays in power – as the Élysée seems to hope.

But if he has been the most valuable, he will most likely also be the last. The system of influence that France has long favoured – based on personal relationships rather than strong institutions – is increasingly confronted with the realities of a rapidly changing world, marked by rising popular aspirations for sovereignty, the waning of Western influence, and the emergence of new powers. Under these conditions, the future of Côte d’Ivoire will soon no longer be decided in the plush salons of Françafrique.