This book’s 50 authors are mostly from the clandestine military network started in 1963 when the Soviet Union received the first 150 South Africans recruits from all over the country, aiming to overthrow the most powerful government in Africa. They included young Joe Modise, who would emerge as the group’s natural leader, and one of this book’s editor, Ronnie Kasrils, his brother in arms.

The recruits’ epic return in clandestine journeys trying to get back to infiltrate South Africa through British and Portuguese colonies resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and injuries, years of prison, years of tough exile, and challenges of disappointments and betrayals. They were a generation of sacrifice. Joe Modise’s style was to eschew publicity, and the man who emerges from this book is a surprise hero of ingenuity, tenacity and leadership skills honed from Sophiatown via Odessa and the Cuban-lead battles in Angola against his own countrymen fighting with their proxy, UNITA.

“At the age of 36 he became the commander of the ANC armed wing”

Victoria Brittain: First of all, why did you choose to do a book on Modise, the least known of the inner circle of the toughest years of the armed struggle in South Africa, and thereafter? And why did you choose this formula of telling the story through 50 voices?

Ronnie Kasrils: Precisely because Joe Modise (JM) was the least known of that leadership; and yet was the most intimately connected and central to the armed struggle over the entire period - launching of the armed struggle in 1961 to achievement of political power in 1994. Apart from being a key operative indispensable to Mandela in the opening phase of the armed struggle, personally carrying out dangerous operations, at the age of 36 he became the commander of Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK), Spear of the Nation, the African National Congress (ANC) armed wing established with the South African Communist Party (SACP). This was in1965 following Mandela’s imprisonment.

Modise held that position until the end of the armed struggle in 1994 and overthrow of apartheid. That made him one of the world’s longest serving guerrilla commanders. While the roles of Joe Slovo and Chris Hani, for example, have been deservedly well documented, at times Chief of Staff and Army Commissar respectively among other roles, their leadership functions were far shorter. A focus on JM allows an interrogation of all the twists and turns of MK’s history.

Modise was not the public persona of men like Slovo, Hani and others, he preferred to work in the shadows. Neither was he as popular with the foot soldiers, although those who worked close to him held him in the utmost regard. There were times when as commander he had to battle to assert military discipline over dispersed and at times near mutinous irregular forces in difficult conditions of exile.

This made him a key target of the apartheid propaganda agencies and their spies, many within the liberation movement, and others ideologically hostile to the ANC and its communist links. Such smears continue to this day.

This examination of Modise’s life and legacy, with the viewpoints of those who worked closely with him, as well as family and former enemies, is not only a vindication of his contribution to an epic struggle, but is essential for South Africans, especially the younger generation, to understand the sacrifices, courage, commitment that brought us freedom.

Victoria Brittain: Can you talk about JM’s class and family background, and in the 1950s his township organising.

Ronnie Kasrils: Modise was born in 1929 in a mixed-race Johannesburg township which shaped his non-racist values. His father was a migrant from Botswana, who worked in a factory, his mother, of mixed race, died when he was 12. He was a bright schoolboy but forced to make a living from age 14, to become a bus driver by the age of 20. By then he was living in Sophiatown, a crucible of defiant black politics and vibrant culture. He embodied the style of emergent street-wise township youth, in sartorial panache and a cheeky jargon called tsotsitaal, which breathed defiance. He was of that post-World War II generation, in an industrialising South Africa, that flocked to the ANC and Communist Party.

Modise soon became a lieutenant to Nelson Mandela in the Defiance Campaign against the newly instituted apartheid laws of the 1950s which intensified segregation and repression. As a newly-wed he and his young wife and daughter were evicted from Sophiatown, along with thousands of black residents to dormitory locations outside cities such as Johannesburg – the forced removal of non-white communities from the urban areas. As a low paid worker, he experienced first-hand both class and national oppression. He proved to be a highly motivated and skilled organiser. His peers recall how Modise would keep up a running commentary as commuters boarded his bus, explaining the cause of their suffering and the need to rise up against oppression.

Some of his detractors have misrepresented Modise’s early activism, alleging he was a gangster whose verbal fluency in tsotsitaal reflected a criminal background. In fact he was a chosen organiser by Mandela and the top ANC leadership and one of the youngest of the legendary Treason Trialists. Johannesburg was a melting pot of ethnic groups drawn to the metropolis from all over southern Africa. Modise reflected the non-regionalist, non-racist, multi-culturalist dynamism of the city, key to forging the inclusive unity of a national liberation movement.

“The training of ANC combatants started in Moscow in 1963”

Victoria Brittain: You two were among those chosen for military training in the Soviet Union, tell us something about that experience and how Modise’s leadership of MK emerged.

Ronnie Kasrils: The training of ANC combatants started in Moscow in 1963 and Odessa in 1964. Over the years specialised training for the ANC and a pantheon of guerrilla movements took place in several parts of the USSR. ANC Navy officers were trained in Baku (then Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic). Pilots studied in Frunze (then Tajik SSR), Political Commissars - in Minsk (Byelorussian SSR). And a major training area for African movements was in the Crimea, where the terrain was more like that of Southern Africa.

The decision to admit ANC comrades for training was made in Moscow, funds were from the state budget, and the training was by the Defence Ministry. I was part of the initial group of 150 MK recruits trained in Odessa in 1964. Joe Modise commanded the group, with Moses Mabhida, a veteran trade unionist and later Secretary General of the SACP, as his commissar.

We were based at a military institute in Odessa for the training of Soviet junior officers, named “Red Banner Combined Arms Command School”. The Soviet staff, commanded by Major-General Chernyshenko, Soviet Ukrainian veteran of the Great Patriotic War against the Nazis, implemented the training programme directed by Soviet Central Committee, and Ministry of Defence, following the request from the ANC leader OIiver Tambo.

Modise and Mabhida trained alongside the rest of us “kursanty” (cadets – military trainees). The preparation was a hybrid of regular and guerrilla warfare. In retrospect we saw how thorough and constantly analysed the Soviet planning was.

“Revolution was not rock and roll”

Our contingent was mainly mid-twenties and from all over South Africa, though mainly the cities. Most were working class. Not many had completed high school, but many had participated in the mass struggles and strikes at home. The entire detachment had the same overall subjects such as guerrilla tactics; handling of weapons from the AK47 assault rifle, light and heavy machine guns, mortars and rocket launches (with plenty of target practice particularly with AK and Makarov pistol); use of grenades; anti-tank and anti-personnel mine-laying; operating in skirmish lines in open terrain and small raiding parties. Some of us even learnt to drive the T34 Russian tanks; others handled heavy artillery weapons. Modise encouraged this, as he said, “guerrilla forces would seize such weapons from the enemy”. Much time was devoted to political instruction.

Our political instructor, Major Chubinyikan, was an unforgettable Soviet Armenian. Revolution, he stressed, was a tough prospect not to be indulged in lightly. Major Chubinyakan insisted that armed struggle should only be embarked on if no democratic liberties existed. He warned that revolution had its setbacks and defeats but once it involved the masses, had the correct theory, strategy and leadership, was invincible. For him, the proletariat was the gravedigger of capitalism. He liked to use the phrases “man to man as wolf to wolf” under capitalism; and “man to man as friend, comrade and brother” under socialism.

The Major told us of the backwardness and poverty of the peasants under the Czarist Empire and strides made by the Soviet Union, the first country to put a human being into space. As a Soviet Armenian he was proud to tell us that before the revolution Armenia was a nation of shoe-shine boys, and now had the highest per capita ratio of doctors and engineers in the world. He had a great sense of humour, saying in English “revolution was not rock and roll.”

We got up at 6:00, with half an hour of physical exercise before we had breakfast and at 9:00 began classes. Practical exercises in the field followed lunch.

Most of our recruits had never met any whites and were now being well catered for beyond their imagination: decent living conditions, hot showers, good meals, all prepared by the staff.

“They taught us to hate and loath fascism and racism in all its forms”

We studied the history of the Great Patriotic War, with a big segment about the partisan warfare against the fascist invaders in all the occupied areas of the Soviet, where people were executed in the hundreds of thousands, including by Nazi collaborators. We learnt of the Nazi collaborator, Stepan Bandera, and his death squads, responsible for massacring hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian communists and Jews. Our instructors came from all over the Soviet Union, and those who were Ukrainian were communists to a man. They taught us to hate and loath fascism and racism in all its forms, to despise imperialism and the capitalist system, and what was termed the shameful colonial system. In political study class there was special focus on the anti-colonial, national liberation struggles, in Africa, Asia and Latin America, to create independent states, freedom and democracy; how to develop the economy once we were free in order to break away from the control of Western Imperialism and neo-colonialism.

Odessa was a cosmopolitan city; and like the eastern part of the Ukraine, including the Crimea, was very Russian. We were allowed into the city on weekends without supervision, and wore civilian clothes, and were provided with pocket money. We were received as honoured guests at the city trade union centre. Our favourite place was the military “palace”, where there were cultural events and dance on Saturday evenings and we would display our African dancing steps to the amusement of the Soviet attendees.

After half a year training in Odessa, we spent three months at a sea-side training camp where we engaged in mock-battles, raids and ambushes. It was very realistic preparation save for the blood and gore.

This was the build-up to Joe Modise commanding the entire detachment over a four-day war game in which he distinguished himself as a leader. This included the crossing of a huge river using rowing boats and dinghies. At the time we couldn’t imagine this as preparation for crossing the Zambezi River from Zambia in 1967/68 against Rhodesian forces, or the Kwanza River in Angola in firefights against Unita in the 1980s. Modise was part of both those difficult campaigns.

I learnt from Modise in later years, how much we owed to that training in Odessa. He and Mabhida with the Soviet staff spent hours analysing the training, identifying shortcomings, aiming at improvements. Our own development of MK training in later years, and also of the other African national liberation movements was rooted in this work.

“Clandestine revolutionary organisation was imperative”

Victoria Brittain: Moving on, please tell us about the very difficult early months of the return from USSR, and the unknown routes towards South Africa across dangerous hostile countries.

Ronnie Kasrils: By the time the first MK groups trained in the Soviet Union returned to Tanzania the ANC faced a dilemma: how to re-infiltrate cadres into South Africa. A large transit area was being established by the Nyerere Government at Kongwa, Dodoma district, some 300 kms inland from Dar Es Salaam, for the armed contingents of the liberation movements based in the country: Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe. By 1965 the ANC’s camp had some 500 trained cadres raring to return to South Africa.

The fundamental problem was that the underground network within South Africa had been virtually crushed by the capture and imprisonment of the internal leadership and the round-up and incarceration of thousands of activists. The original plan was that the initial complement of cadres trained abroad would find safe reception on their return and political links with the masses. By 1965 that plan, linked to organised underground structures, no longer existed. This was the main problem facing the ANC, compounded by the vast distance from the country, through hostile terrain of colonial Rhodesia and Mozambique, and British oversight of Botswana, Swaziland and Zambia. This cordon sanitaire was reinforced by a network of enemy agents and informants that reached within independent Africa and even within all the liberation movements, which made clandestine revolutionary organisation imperative.

As months dragged by patience among MK was sorely strained and gave rise to tensions and discontent with the leadership, obliquely seen as living a softer life in the capital, Dar Es Salaam, and focussing on international conferences instead of the home front. There were divisions too inside the camps, but in the ANC’s case, these were more of a regional than a tribalist character. A great deal of criticism was aimed at Modise, given his responsibility for MK, yet he was working like the proverbial Trojan, seeking to find answers to the unforeseen new situation.

“Many young lives were lost”

In 1966 things changed when Zambia became independent. Kenneth Kaunda’s government allowed the liberation movements to open offices in Lusaka and opportunities arose for guerrilla infiltration south. Modise seized the opportunity. In fact he was so key to forging a fighting alliance with Rhodesia’s opposition guerrillas in ZAPU’s armed wing, ZPRA, that in the joint incursions fording the Zambezi into Rhodesia, ZPRA officers – somewhat disillusioned with their own political leaders – referred to him as their commander.

The attempt by ZPRA to establish bases within the country, and MK to infiltrate guerrillas from there into South Africa during the 1967-68 joint operations, saw fierce encounters, but failed in the objectives. Yet the heroism and skill of African freedom fighters inflicting casualties in battles against white supremacist forces inspired the masses in both Zimbabwe and South Africa. There are many eyewitness accounts in the book about Modise’s leadership qualities, his bravery and resourcefulness. These range from his readiness to lead reconnaissance units into enemy territory instead of directing operations from relative safety, to solving practical logistical problems such as dangerous river crossings. One of these was his innovation in improving the buoyancy of rafts carrying heavy material by incorporating empty oil barrels. Success was elusive. ZAPU had no organised networks within Rhodesia, the terrain through the Zambezi valley and beyond was extremely difficult, lacking population in the immediate proximity, hot and dry, lacking water resources on the route south, which gave huge advantage to the enemy’s use of helicopters and spotter planes. Many young lives were lost in that period and over the years against a formidable foe, aided and abetted in particular by Britain and the USA. Yet in that Zimbabwean incursion of 1967-68, a generation of freedom fighters showed their contempt for death in the struggle for liberation.

Victoria Brittain: Can you talk about the extension of Modise’s role across the region.

Ronnie Kasrils: The Zimbabwe campaign revealed Modise’s personal political acumen in developing a fighting alliance with ZPRA which would have favourable consequences for further cooperation once Zimbabwe became free in 1980. A turning point came in 1975 when Angola and Mozambique became independent, and in 1976 there was an influx of South Africa’s youth into MK following the Soweto uprising. As a result, opportunities and demands were exponentially raised. The challenge was whether the ANC and MK could meet the historic revolutionary demand.

The collective united movement had survived the most difficult years, with accumulated experience to lead a new situation. Oliver Tambo had held the Movement together with his outstanding political qualities. Joe Modise, who served Tambo loyally, had the special responsibility of the armed struggle. And assembled around him were a coterie of outstanding peers such as Joe Slovo, Moses Mabhida and Mzwai Piliso, and the younger generation of the early 1960’s, prominent among them Chris Hani, Jackie Sedibe, Mavuso Msimang, Thabo Mbeki, and many more.

The first challenge was the recruitment into MK of most of the young people who had left South Africa in search of weapons to fight the Apartheid regime. They gravitated to the ANC, because of its historic record and known organising ability.

“The Soviet Union was the main source of arms shipments”

The ANC had managed to maintain its tenuous organisational presence in states such as Botswana, Swaziland and Lesotho directly under enemy eyes. These links were now reinforced to handle the clandestine recruitment and channels north. Mozambique became the strategic forward base of for the reception of recruits and their subsequent re-infiltration as trained cadres.

Modise displayed his organising ability criss-crossing the region, using the ANC’s party-to-party political contacts developed over years with Tambo, guiding the development of new clandestine travel routes, and above all the establishment of training camps in Angola. With Tambo and Joe Slovo, he brought Cuban, GDR and Soviet instructors to help the training in Africa, and most importantly, advanced training for MK in those socialist countries.

The Soviet Union was the main source of arms shipments. Modise arranged the detailed reception of this cargo; and among other measures set up front companies to transport the weapons south. By 1977 the first trained recruits from the 1976 cohort were moving back into South Africa to restart armed operations within South Africa, the first time this was effectively done since the early 1960s.

“The recruitment of a group of Palestinian engineers”

Modise operated out of Lusaka, Zambia but was seldom home. This was a small house in a Lusaka township, shared with his wife Jackie Sedibe, a fellow MK commander, responsible for military communications. He assigned operational responsibilities with Slovo based in Maputo on South Africa’s eastern flank, whilst he handled Botswana on the western flank. It was dangerous entering the forward areas, but Modise often visited Botswana, and on one occasion was arrested on an arms smuggling charge, serving almost a year in prison.

One example of his internationalist contacts, and his ability to develop them, was the recruitment of a group of Palestinian engineers employed in the Botswana diamond industry, who had Israeli passports and looked like Jews. They carried out reconnaissance for him inside South Africa.

His working-class background is highlighted in the many anecdotes of how Modise would lead comrades in the camps in cultivating vegetable gardens and constructing buildings. A young recruit in an Angolan camp recalls how JM got them digging with picks and spades, and forming a human chain, passing water in a bucket from the river to the newly prepared vegetable patch; not simply giving instructions but participating in the tasks. Sometimes he was incognito, as shown in the story of a new recruit in a Maputo transit house having noticed a worker quietly busy over several days repairing the roof, only to discover this was the MK commander, Joe Modise, when he subsequently met him in Luanda. JM would pop up all over the vast region. Underground intelligence officer, Mohammed Timol, married to a local woman, recalls JM enjoying a prawn and chicken dinner, pressing her for the recipe, and quizzing her about all the facts of the furniture business she ran. Spencer Hodgson recounts JM visiting SOMAFCO (Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College), the ANC’s education and agricultural hub in Tanzania, where he would show great interest in the details of construction of infrastructure, maize cultivation, and live-stock breeding.

“Modise would wash his own clothes”

Modise was no regionalist, and although those deployed home would best survive in their areas of origin, he would send them elsewhere to reinforce national identity. He was notably non-racist, choosing Indian, mixed race and white comrades to work alongside him. He also ensured that women were part of MK structures at all levels, and was greatly respected for his approach on gender issues. An MK woman recruit, Ribbon Mosholi, saw JM as “a typical South African man” however “he kept to the times when it came to the advancement of women … and he would go out of his way to promote women.”

Those who fostered gossip about Modise were very often disgruntled people who had fallen foul of him over poor discipline. As commander of the army, it was necessary to be strict about discipline, and his burly presence and gruff voice, unnerved many, and provided grit to the rumour mill. But those who came close to him, even ordinary foot soldiers when it came for time to relax, were delighted to find that he came down to their level in chatting about politics or sport, often throwing in tsotsi phraseology in his jokes. Pallo Jordan, one of the 1960’s generation, and a leading intellectual, recalls how in a Luanda residence, Modise would wash his own clothes, and joke with him about the allure of a regular army where a commander had a batman to take care of such chores. Modise’s empathy for the troops could shine through unexpectedly. Garth Strachan, a relatively junior commander, recounts Modise seeking him out to express condolences on hearing his sister has died back home, and remarks: “This small gesture was very important to me and suggested that he was anything but the callous, hardened military man, which the role he had to play conveyed.”

JM’s very close personal relations with ZPRA/ZAPU comrades from Zimbabwe, previously referred to, provided very favourable links after independence in 1980. The rival ZANU of Robert Mugabe won the election, and although ZAPU worked with ZANU as the junior partner in government, and amalgamated into ZANU PF, the ANC had to work with discretion in receiving political recognition and a strategic presence in the country. The huge trust ZPRA comrades, now within Zimbabwe’s newly established defence force, had for JM, saw several hundred MK cadres being amalgamated within the army at its inception under the noses of the British and Rhodesian scrutinisers, and assisting other MK cadres operating clandestinely across the borders into South Africa.

“An example of international solidarity”

The closeness of the ANC-ZAPU alliance was an outstanding example of international solidarity and was one of the fruits of Modise’s and others’ work over many years. The year before Zimbabwe’s freedom he had accompanied Tambo and a delegation to Vietnam, to cement relations and study the lessons of that country’s victories over French colonialism and USA imperialism.

The years of ANC focus on the military alone was because of the near destruction over years of internal political structures. Modise, like all the leadership, was quick to adapt in the restructuring of a politico-military approach when in the early 1980s popular internal organisations emerged alongside a progressive trade union movement – the United Democratic Front (UDF) and Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU).

But, while there were advances on the home front, the ANC was facing challenges across the region as South Africa was destabilising the frontline states: a coup in Lesotho; an agreement forced on Mozambique in 1984 (The Nkomati Accord) for the expulsion of MK, and similar in neighbouring Swaziland. In Angola and Mozambique, South Africa had built up armed terror groups, Unita and Renamo.

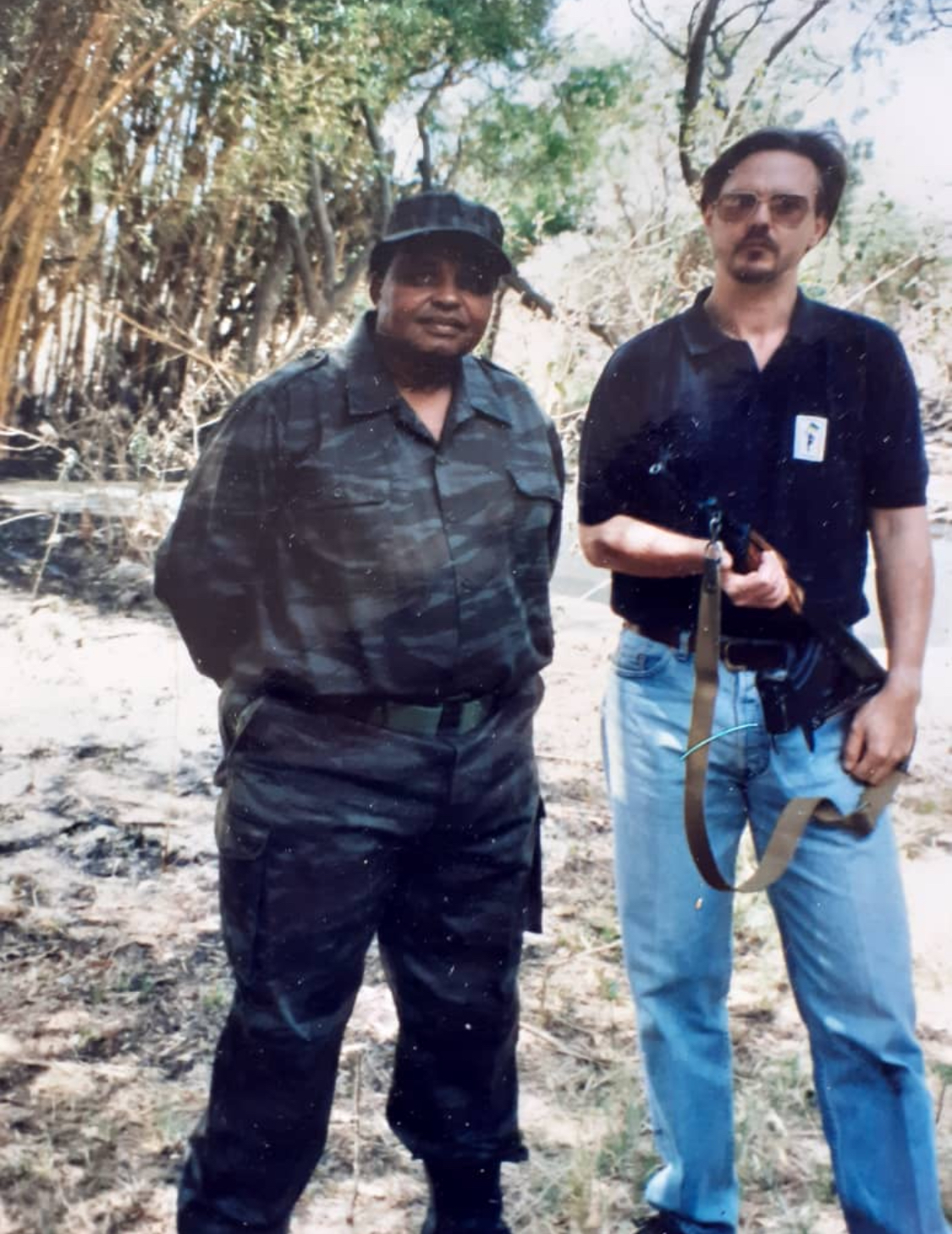

MK in Angola assisted government forces. Modise himself directed some of MK efforts, and as in Zimbabwe in 1987/88, was insistent on being in the firing-line with his troops. By 1988 with the assistance of Cuban forces the Angolans defeated the SADF, forcing them out of the country and opening the way for the independence of Namibia. I was with Modise in Cuba when he received the personal appreciation of Fidel Castro for MK’s contribution in confronting the SADF’s proxy Unita, and providing the Angolan-Cuban forces with significant intelligence about the SADF’s battle plans, personnel and equipment.

“Gaining the confidence of the former adversary”

Victoria Brittain: When was the political turning point to negotiations?

Ronnie Kasrils: By the mid to late 1980s the emergence of the UDF and COSATU, coinciding with South Africa’s military defeat in Angola and consequently Namibia’s independence, the balance of forces had titled significantly in favour of the democratic breakthrough in South Africa. This was clearly the consequence of the mass struggle of the people, reinforced by armed actions, an underground network and the significance of international solidarity which isolated the apartheid regime.

This forced the regime into the negotiations for a peaceful transition to change. The business community had pressurised the regime to come to terms for change, as did the Western powers. There was agreement among the country’s economic elite, which reached into some upper echelons of the military, that the opening for a reformist change needed to be seized. That the liberation Movement accepted the negotiation route to political power was not just Mandela’s considerable influence, but a necessary step forward to redressing the socio-economic issues in the country. Modise together with Hani, and Slovo, who had become General Secretary of the SACP, accepted the negotiated route, not as individuals but as leaders of key military and political formations.

Victoria Brittain: How did Modise move from the war years into the new relationship with the apartheid era Generals?

Ronnie Kasrils: Mandela and the ANC leadership showed their faith in Modise, by giving him the responsibility of negotiating the transition of military power with the SADF generals. At the political level it had been agreed that the former South African army and Bantustan armies, would be integrated with the ANC’s MK and the barely functioning PAC’s armed wing APLA. Tensions were very high, with speculation of a coup by sections of the apartheid military and police. These groups were believed to have been implicated in fermenting the dirty war that had claimed over 20,000 lives in black-on-black violence between 1990 and 1994 in an onslaught on the African townships with killings of activists, notably the assassination of Chris Hani in 1963. This was part of an ultra-right strategy aimed at collapsing the negotiations, weakening the ANC and destabilising the country.

Modise’s intelligence teams had good insight into the SADF; and into divisions between the Part Time and Permanent Force. The former were the vast numbers of the SADF, with many in command structures who were from the middle class, business sector, interested in change. Modise won their trust, as he later impressed the generals of the Permanent Force who held power, for his focus on building a professional military.

Gaining the confidence of the former adversary was key to the smooth transformation that followed, and one of his greatest achievements. What they really appreciated was Modise’s intent to build a modern defence force with equipment to replace the obsolete weapons they felt had lost them the war in Angola because of international sanctions.

As the Chief of the Navy put it: “We in the armed forces were delighted when [Modise] became our Minister of Defence…despite his political position , [he] remained a soldier first and foremost… As such he never treated ex-SADF personnel unfairly.” The chief of the old SADF, Georg Meiring, was appointed by Mandela as commander of the new, reconstructed SANDF. He was very conservative and tried slowing down the transition, aiming to restrict just three of the MK command to the rank of generals. Modise would have none of that and insisted on eighteen, including for the first time in South Africa’s history, a black female. By 1998 Meiring opted for early retirement and a MK general became chief of the SANDF. I reminded Modise how one of Meiring’s right hand men had blurted out after an early round of negotiations that “South Africa could have one of the best armies in the world – white officers and black soldiers.”

“To transform of the military to serve as defence for a democracy”

Victoria Brittain: As Minister of Defence in Mandela’s government what were the key changes he made?

Ronnie Kasrils: The key was a comprehensive transformation of the military to serve as defence for a democracy. He created a civil Secretariat of Defence, serving the Ministry and ending the years of military service deciding their own budget, control mechanism over finance, policy and doctrine, and avoiding parliamentary oversight. The conscript system was abolished. Gender equity and a civic education programme were introduced to create a new defence culture.

Modise signed the international agreement to abolish the use of anti-personnel mines, and made the Defence Force subject to agreements within the OAU’s mandate and peace keeping operations. This won regional and international respect for South Africa’s new military.

Victoria Brittain: When ill health meant Modise stepped back from politics in the Thabo Mbeki years how did it happen that his reputation was trashed in the media and accusations of corruption came even from within the ANC, so much at odds with this book’s story of the man?

Ronnie Kasrils: I already referred to attempts to smear Modise’s reputation, and those of others in leadership, during the years of exile and struggle. During the halcyon period of Mandela’s Presidency, and the manner in which Modise won the trust of the former SADF, his popularity was at a high point. The Defence Review, leading to the procurement programme for new military equipment, received unanimous parliamentary approval.

It was soon after Mandela and Modise’s retirement from office in May 1999, the latter owing to ailing health, that contract for defence purchases with foreign companies, arising out of Modise’s Defence Review, were signed off. By 2005 the financial adviser to Jacob Zuma, Mbeki’s deputy president, was found guilty of corruption linked to a contract with the French armaments company, Thales. Hearings in parliament began, rumours abounded, concerning possible corruption at government level. The unscrupulous, and some who were misled, pointed fingers at the likes of President Mbeki and Modise.

Despite three state investigations into Cabinet’s role, including one by the Auditor-General, and a Commission of Enquiry, no such evidence emerged. The media, and several commentators who wrote books on the issue, dredged up all the malicious police-based smears of the past, about ANC corruption in exile. Modise did not die a wealthy man, and his widow, General Jackie Sedibe (rtd), worked until she was almost 80, to maintain a modest lifestyle for her and the children.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism: