A profound analysis of the unscrupulous endgame of the Belgian colonial empire of Congo, is at the heart of The Lumumba Plot. Among the book’s many chilling revelations is that the President of the United States, Dwight Eisenhower, ordered Lumumba’s killing, and that Washington’s Cold War obsession meant they misread Moscow’ lack of interest in Congo and Lumumba’s strong interest in working with the Americans.

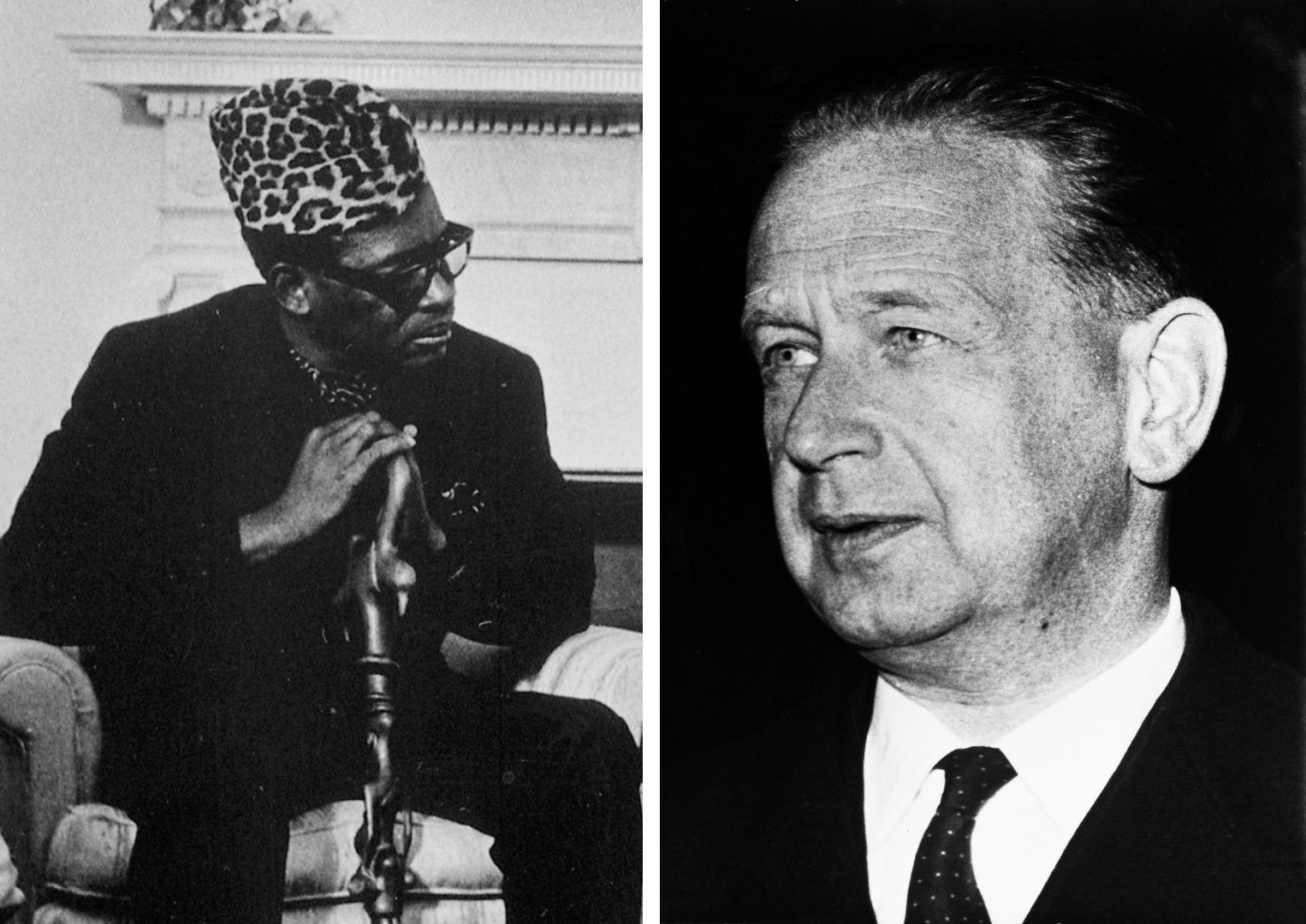

Stuart Reid’s deep research in the cable traffic of the major players – some only released by the State Department in 2023 – exposes deep disfunction. And in some cases the private letters and papers or their children’s memories, reveal personal characteristics and ruthless decision-making not previously known. Men like UN chief Dag Hammarskjold, Joseph-Desire Mobutu Lumumba’s treacherous friend, Moise Tshombe the Belgian tool of Katanga separatism, and the CIA’s dirty tricks man Larry Devlin, come to life vividly as they juggle their way through the fraught years. The tragedy of Lumumba’s assassination was, Stuart shows, the tragedy not only of his country’s, but also the continent’s, failed development then and for decades afterwards as the United States made Mobutu’s Zaïre the tool of imperialism and the model of corruption.

“This story should not be boring !”

Victoria Brittain : Can you explain how you came to write this very ambitious book in a new area for you ?

Stuart Reid : It all began with a 2014 Africa visit. I was writing an article for Politico Magazine about Russ Feingold, a former U.S. senator whom the Obama administration had made a special envoy to the Great Lakes region of Africa. I was immediately taken with the place and started reading up on its history. The more I read, the more I realized there was a great story here about the country’s traumatic birth. The Congo crisis was front-page news in the West in 1960 and 1961, only to be largely forgotten afterwards to a mainstream audience. The United States played a massive role in it. And yet I had barely heard of the episode. And then, of course, there were the larger-than-life characters: Mobutu, Devlin, Hammarskjold, and, above all, Lumumba himself.

Victoria Brittain : You acknowledge the assistance of 17 research assistants, including in DRC and Belgium, and also the contributions of more than a dozen friends and scholars who read the manuscript and made one key introduction, plus a brilliant editor. Could you say something about how so many people invested themselves in this book ? And how, although you point out you dont have a PhD, you were clearly writing an academic book, though actually it reads like a cant-put-it-down novel ?

Stuart Reid : Writing a book is much more of a team endeavor than I had imagined. I needed to hire people to, say, look through a box at a distant archive for me (especially since much of the research took place during the pandemic) or format endnotes. And during my four trips to Congo, I needed to work with local journalists to arrange interviews. Then there was the editing and fact-checking process, of course. And finally, I called in favors from friends, family members, and professional contacts to act as pilot readers for the book. That was tremendously helpful. Everyone had useful comments.

My goal for the book was for it to meet academic standards when it comes to rigor, accuracy, sourcing, and so on – but also meet my own literary standards. The two goals are not mutually exclusive, as I hope the book proves. A story about such dramatic events and fascinating characters should not be boring!

Victoria Brittain : Your 120 pages of notes reveal the extent of CIA, State Department, White House, UN and Belgian government documents consulted, private letters, as well as all the books in your 10 pages of bibliography, 32 interviews by you as well numerous historical ones. Could you say which were the outstanding golden sources for you ?

Stuart Reid : One key source was the trove of cables that the State Department belatedly released in 2013. At long last, one could read the day-to-day communications of the CIA and the State Department from Washington to Leopoldville as they reacted to and shaped events. And very important from a narrative perspective, were my interviews with people who were alive at the time. Lumumba’s daughter Juliana, for example, told me about her memories of living under house arrest—little telling details that make the story come alive.

“In 1960, Mobutu a nervous colonel”

Victoria Brittain : There are two key characters in particular who you draw with a depth and understanding that I have not read before, Mobutu and the UN’s Swedish Secretary General Dag Hammerskjold. Could you say a bit about each of them ? Mobutu in his decades of power became a stereotype. But you have given us a much more interesting picture of the high psychological cost of years of Belgian and US moulding. On Hammerskjold, one detail from the last of his four visits to Congo underlined his rigidity and total cultural/personal gulf with Lumumba when he refused to read his moving letter from prison in Camp Hardy and « turned red ». What did you end up feeling about them by the end ?

Stuart Reid : What I found so interesting about Mobutu is that the Mobutu of 1960 and 1961 is very different from the Mobutu the world would come to know later in the 1960s and 1970s. He had yet to become a cartoonish, all-powerful dictator ; he was a nervous colonel who couldn’t make up his mind. Keep in mind how young he was : 29 years old at the time of independence. But by chance he ended up in the key position as army chief of staff. So, everyone was whispering in his ear and putting him under conflicting pressures – the Belgians, the Americans, the UN, Congolese ministers, his fellow officers.

Hammarskjold in many ways was also a torn man. One the one hand, the UN was still in many ways a U.S. dominated institution, Hammarskjold was a man of the West, and he really came to detest Lumumba. On the other hand, he was feeling increasing pressure from African and Asian countries that supported Lumumba. So his policy toward Lumumba shifted over time, becoming more accommodating of him by necessity. A gap between the views of the U.S. and the UN opened up. Ultimately, however, the UN failed to intervene to save Lumumba’s life – which it could have done.

Much has been written about Hammarskjold’s death. My book is not a book about the plane crash, to be clear, and interested readers can seek out those books for themselves. That said, my take is that we will never know with certainty what really happened, but a lot of the conspiracy theories are far-fetched, sloppily evidenced, or mutually exclusive. This is what I wrote in the book : “The most likely explanation for the crash is that Hammarskjöld’s plane went down for the same reason most planes did in 1961: as a result of pilot error. Hammarskjöld’s plane was the sixth DC-6 to crash that year. It was not the first serious aviation disaster for the UN operation in the Congo, nor would it be the last.”

Victoria Brittain : What can you say about Larry Devlin, the CIA station chief in Congo ? His extraordinary hold over Mobutu, the CIA’s almost bottomless funding and access to CIA operatives such as American Sidney Gotlieb, Luxembourgish Andre Markel and French David Tzitzichvili to carry out dirty work, are still sobering however well you know this story, and will come as a shock to those who never knew it.

Stuart Reid : It really does read like something out of fiction, doesn’t it ? What I found interesting was the mix of competence and incompetence on the part of the CIA. One the one hand, you have these blundering European criminals hired by the CIA who accomplished nothing, and a harebrained scheme of injecting poison sent from Washington into Lumumba’s food or toothpaste that turned out to be impractical. Devlin himself had a paranoid view of the Cold War reality : for example, he imagined that the Soviets could “use the Congo as a base to infiltrate and extend their influence” across Africa. But when it mattered, the CIA was extremely decisive : namely, in backing Mobutu’s coup and greenlighting the sending of Lumumba to his death.

“Eisenhower ordered the CIA to kill Lumumba”

Victoria Brittain : Can you describe how the order for killing Lumumba came from US president Eisenhower himself. It was keenly supported by powerful racists in power in Belgium, such as Harold d’Aspremont, head of the Belgian mission to Katanga, and many officials in the US. And please talk about the sequel to that consensus, with Kennedy’s election and the early promises that Africa’s independence would be a key policy plank in his administration. There was a moment when Lumumba it seemed could have been saved with an intervention from Washington. But that never happened and the liberals in the Kennedy entourage were outgunned leaving US foreign policy crippled by similar illegal failures such as the Bay of Pigs and Vietnam.

Stuart Reid : The key meeting was August 18, 1960. Eisenhower met with the National Security Council. Congo and Lumumba came up. The president, according to a note taker present, “said something – I can no longer remember his words – that came across to me as an order for the assassination of Lumumba”. We have good reason to believe this note taker for a number of reasons. One, he testified to that effect. Two, I found another official’s hand-written notes from the meeting, which show a big “X” next to Lumumba’s name (which is admittedly inconclusive evidence). Three, and most important, what happened next : the president’s national security adviser had to nag the head of the CIA about the order from the meeting, following up to make sure an assassination operation was in the works. Then, when the poisons arrived in Congo, the chemist delivering them – Sidney Gottlieb – told Larry Devlin that the order for the assassination came from Eisenhower. So there’s really no doubt in my mind that Eisenhower ordered the CIA to kill Lumumba, despite what Ike’s defenders like to say.

John F. Kennedy won election in November, but wasn’t sworn into office until January. During the interim, there were signs from some of his advisers that they were going to take a less hardline approach toward Lumumba. There was a real possibility that Lumumba, now imprisoned, would be freed and brought back to power. This possibility struck fear in the heart of Mobutu and his henchmen, as well as in the heart of the CIA’s man in the Congo, Larry Devlin.

Victoria Brittain : UN officials’ struggles for power versus the US as the Congo unravelled is an interesting and complex strand in this debacle. Poor communications and lack of experience in an unprecedented and vast endeavor were only part of the problem which had its fundamental roots in Western attitudes of racism. It would be good to hear your views on that, from this past history, and so relevant today.

Stuart Reid : The year 1960 was a time of transition for the UN. During the Korean War, the U.S. intervention in Korea had been officially a UN operation. In early 1960, the UN was still a vehicle for U.S. interests. Many of Hammarskjold’s top advisers were American. But the composition of the organization was changing. All those new African members were entering. The Soviets were coming to regret authorizing the UN operation in the Congo. And so over the course of the Congo Crisis, friction developed between the U.S. and the UN. Caught in the middle of them was Ralph Bunche, an American working for Hammarskjold.

“The Lumumba plot was a major part of the Church committee”

Victoria Brittain : Can you please explain how in 1975 a large part of this story, with deeply shocking revelations, unexpectedly came into the public domain. And also can you talk about how Devlin the CIA station chief in Congo, giving evidence, typically obscured his own key role in keeping Washington out of the loop until it was too late to save Lumumba. And about how Richard Helms deputy to CIA chief Richard Bissell was, unbelievably not able to remember what the problem with Lumumba was.

Stuart Reid : A lot had changed from 1960 to 1975. The Watergate Scandal. The Vietnam War. Details about the CIA’s questionable covert activities had leaked to the press. So the Senate voted to create a special committee to investigate the intelligence community’s excesses on many fronts. The chair of that committee – Senator Frank Church of Idaho – thought that details about the CIA’s assassination efforts would best capture the public’s imagination, so that was the subject of its first report. And the Lumumba plot was a major part of that report.

Devlin was one of several people who played a key role in Lumumba’s death. He greenlit the transfer of Lumumba to Katanga run by his historical enemy Moise Tshombe, where everyone knew he would be killed. And, worried that Washington would tell him to intervene and stop that transfer, Devlin kept his superiors out of the loop (even as he updated them about other matters). He feared, correctly, that Washington would cite the impending presidential transition as a reason to preserve the status quo in Congo – all important decisions had to wait until Kennedy took office.

As for Helms, his quotation to the 1975 Church Committee is astonishing : “I am relatively certain that he represented something that the United States government didn’t like, but I can’t remember anymore what it was”, he said. He asked his interrogators for help. “Was he a rightist or leftist ? . . . What was wrong with Lumumba ? Why didn’t we like him ?” In 1960 and 1961, Lumumba was an object of intense fear in Washington, and yet a little over a decade later, at least one senior CIA official couldn’t remember his ideology.

“Lumumba probably would have presided a neutral country”

Victoria Brittain : Could you spell out how you feel the US establishment mis-reading of Lumumba’s wish for good relations with the US, even asking for US troops to help him keep his country together in the face of Belgian dirty tricks in Katanga, so deeply poisoned Africa’s post-colonial history in the aftermath of his death ? With Mobutu, the US used the Cold War to divide the continent, and Congo along with Morocco, were the US key clients. For example, can you imagine that if Lumumba had lived he could have been a key partner in the ardent wish to make Non-Alignment the story of those Cold War years. For instance, in that case the US intervention in Angola’s future independence (so well documented by John Stockwell from inside the CIA) would not have given apartheid South Africa those extra years, with their war which ravaged the Front Line States, killed many thousands of a generation of South Africa’s leaders and destroyed Angola.

Stuart Reid : Washington saw Mobutu as on its side in the Cold War, which for the most part was true. But the funny thing about Mobutu as a U.S. client was that America didn’t even get what it paid for. He expelled two U.S. ambassadors because he thought they were insufficiently deferential. He invited in hundreds of military advisers from Communist North Korea. And he even once accused the CIA of plotting to overthrow him.

It’s a fascinating counterfactual to imagine what would have happened had Lumumba stayed prime minister and survived. As I wrote in the book, “Had he been given a chance to stay in office, he probably would have presided over not a Soviet client state but a neutral, if left-leaning, country”. But of course, the Congolese were never given the chance to experience that version of history.

Victoria Brittain : Could you please sum up your own feelings about Lumumba after all these years of so closely studying him and the political context he was plunged into ?

Stuart Reid : My goal was to scrape away the mounds of lies, mythology, and conspiracy that have accumulated around Lumumba over the decades. I strove to present the man in his own words, in the context of his own times, and through the prism of his own experiences. The result was, I hope, a portrait of the man that dispensed with nostalgia, showed him in all his complexity, and yet explained his appeal and conveyed his humanity. His murder was a personal and national, even international tragedy.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism :