They were years of boundless Black ambition, optimism and creativity – an era of idealism. French draws a many layered portrait of Ghana’s visionary independence leader Kwame Nkrumah’s pioneering role in belief of the Continent’s transformation by cooperation and unity - Pan-Africanism. The book reveals too unsparing detail of the ruthless sabotage by American and British economic interests, which led to Nkrumah’s ouster.

As with his award-winning previous book,Born in Blackness, (2023) French transforms history with the great breadth of his scholarly research and his accessible writing style. He has been professor of journalism at Colombia University since 2008 and was previously New York Times bureau chief in Central America and the Caribbean, West and Central Africa, Japan and the Koreas, and China, based in Shanghai.

Victoria Brittain : What was the spark for this book?

Howard French : Like all my books, this project arose through a confluence of factors. The first was my own lived experience of Ghana and of the continent, generally, including the family background you mention. Bob Weil, my editor, did indeed tell me that he badly wanted to publish a book on Nkrumah. Our conversation about this began with his request for suggestions of people I could refer him to as authors. After much back and forth, he finally said that his hope all along was that I would do the book with him. I wasn’t sure that I wanted to proceed until I began to do some serious preliminary research. Books are big commitments. My initial reluctance was based in part on the notion that I already knew the Nkrumah story well, but the applied research revealed new dimensions to the story that I didn’t know or understood poorly. These ended being the things that carried the book for me. The first was the deep history of Pan-Africanism that Nkrumah drew from, which is an extraordinary story in and of itself. Black people are generally not included in mainstream intellectual histories of the world, but the fires of Pan-Africanism were kindled during the struggle against the enslavement of Black people. They drew from an extraordinary lineage of thinkers going far back into the 19th century.

The second big narrative current in the book involves the thick and busy cross fertilization between the African liberation movement and the struggle for civil rights in the United States. Each was of vital importance to the other, and it is extraordinary how little this tends to be remembered on either side of the Atlantic Ocean.

African leaders discovering the world

Victoria Brittain : Nkrumah’s dramatic leap from a remote village, including an episode as a stowaway on a ship, into a Black American university and political life, through chance kindness of strangers, seems quite remarkable?

Howard French : One of the many striking things about some of the most prominent leaders of the independence struggle in Africa is how little some of the most important figures knew about the wider world when they set out on the path of political engagement. Nkrumah knew little about African Americans and the details of their fight for citizenship in the United States. Patrice Lumumba, who is an important secondary character in my book, and whom I’ve recently written about here [https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2025/09/25/a-damn-nuisance-patrice-lumumba/], knew even less about the world, and seems to have been confined to the narrow realm of life in a colony dominated by tiny Belgium. In 1935, Nkrumah arrived in the United States to begin what would become a decade of study there, and his first stop on the way to Lincoln, a historically Black university, was Harlem, which was then not far removed from being a global capital of Black thought and political effervescence. This seems to have taken Nkrumah aback but also began his awakening.

Victoria Brittain : Nkrumah spoke of Marcus Garvey as the most important influence on his life, how about Kwegyir Aggrey, W.E.B. Du Bois, George Padmore, CLR James, later Julius Nyerere?

Howard French : Each of these extraordinary figures played crucial roles in Nkrumah’s political evolution. So much so that I cannot single out one as his biggest influence. Garvey lit a light bulb in Nkrumah’s mind about Pan-Africanism even before he arrived in Harlem. Nnamdi Azikiwe, who would later become Nigeria’s first president, was a crusading newspaper editor in Gold Coast while Nkrumah was still a young student there. He also helped stir Nkrumah’s Pan-Africanist thoughts. Azikiwe and Aggrey, another fervent promoter of pride in Blackness, both encouraged Nkrumah to study in the US. James nourished Nkrumah’s sense of revolutionary struggle. Padmore schooled Nkrumah on the practical aspects of liberation activism. Horace Mann Bond constructed the bridge to the African American freedom struggle that became so important to Africa’s history. Du Bois hovered as an eminent presence throughout. In his landmark book, Black Reconstruction in America, Du Bois called the post-Civil War period known as the Reconstruction, “The finest effort to achieve to achieve democracy for the working millions which this world had ever seen.” Du Bois lived the final stage of his long life in Ghana and is buried there, and I am confident that by that time he would have revised this statement to say that Africa’s emancipation from European colonial rule had risen in importance well above the American watershed of Reconstruction.

Building nations against local chauvinisms

Victoria Brittain : You use the phrase “imagined communities” as a useful insight into the small-scale identities of ethnicity, language, kinship, class to highlight Nkrumah’s difficulties with the new politics of independence, can you expand that idea? Nkrumah’s humble background and gift of oratory honed in Black churches in the US set him apart from the class of Ghana’s politicians didn’t it?

Howard French : In the early parts of my book, I trace the ways that Nkrumah’s eventual insights into Pan-Africanism were shaped by his upbringing, as a member of a demographically insignificant linguistic minority, the Nzema, whose population had been split in half by the colonial border between Gold Coast and Ivory Coast. Nkrumah’s identity as an Nzema allowed him to avoid being coded as a member of one of the large and historically rivalrous groups in the colony. His humble background, as you say, also endowed his facility for speaking to the common people. His years in America, including stints as a guest preacher in Black churches, also fed this proclivity. Pan-Africanism was just one of the ideas that fueled Nkrumah during his rise. Another was that to build viable nations (as a steppingstone to federations and other bigger, perhaps continental polities) Africans had to learn to discard local ethnic chauvinisms. Modern scholarship has done a very good job of showing how Britain and other European powers helped invent and cultivate what is still often tribe as a means of divide and rule. The work of Mahmood Mamdani is particularly incisive on this topic. Nkrumah intuited all this decades beforehand. Although his membership of a small group helped him avoid the pitfalls of identity politics to some extent, his entire rule was marked by different groups, the Asante, the Ewe, and northern communities to resist centralized government, and often violently.

Victoria Brittain : Can you talk about the All Africa PC in Accra in 1958? AAPC was one of the most interesting and important events in Ghana’s independent history.

Howard French : African delegations came from far and wide to brainstorm and share encouragement about liberation. A possibly underrated feature of this moment is how Nkrumah had begun drawing lessons from political struggles underway in Egypt and North Africa about their struggles for freedom from European domination, and about the possibilities of federation. It was at this event that Nkrumah, in turn, began to exert a broad practical influence over the political direction of the continent. The most obvious and direct example of this involved Patrice Lumumba, who arrived in Accra as a politically naïve and strikingly moderate activist and was quickly galvanized through the speeches of Nkrumah, Frantz Fanon and others.

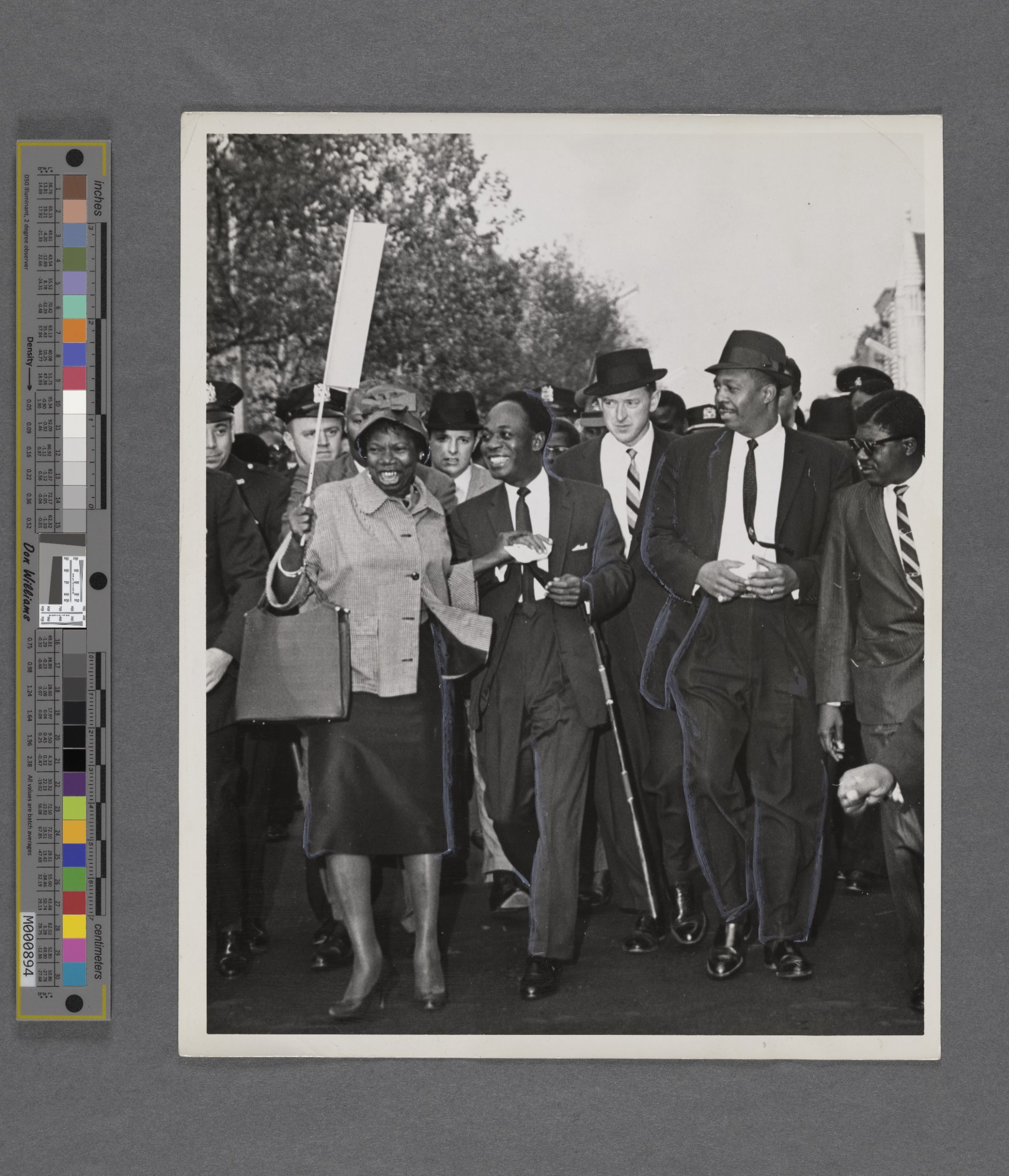

Victoria Brittain : How do you see the impact on the US Black community of the African push for decolonisation, and of Nkrumah? You use the phrase, “He was Obama before Obama floated down the Air Force One staircase – Blacker, cooler, and seeming more unselfconscious…”

Howard French : Recently, I read an obituary in the New York Times of one of the relatively little remembered heroes of the American civil rights movement, one of the young people who risked violent attack and jail to perform sit-ins at segregated luncheon counters in the South. In my book I quote from an essay by James Baldwin in which he says that this sort of courage had been inspired by the brave and peaceful example of Africans pushing for and winning their liberation, beginning with Ghana. Africa occupied a very large place in the American imaginary in that era, totally unlike today. Baldwin also describes the strong pulse of pride that African Americans felt when seeing photos or footage of Nkrumah descending the staircase of an African airliner flown by Black pilots.

London and Washington at the helm

Victoria Brittain : How do you see the colonial powers’ behaviour in this period?

Howard French : All the European powers were taken aback by the strength of African sentiment in favor of independence after WWII, and by the rapid rise of independence movements. Once they began to understand there was no way of turning back the clock, which occurred at different times depending on the colonizer, they generally wanted to have their cake and eat it, too. That meant promoting accommodationist elites, as with J.B. Danquah and Ghana, or pushing for new dispensations that would grant a superficial independence, which retaining formal control over the most important levers of power, treasury, security, foreign relations, etc. Britain, France and Belgium all experimented with the latter. The Gold Coast was the second most important source of foreign exchange for an economically flattened Britain in the immediate postwar era, and London didn’t want to lose this. It also didn’t want to see Ghana industrialize, because that would make for a more independent nation, and was seen as bad for British business. In the early 1960s, under Kennedy, the US became the most important factor in mediating Ghana’s place in the world. Any answer on this question must inevitably be highly compressed, but Kennedy was broadly sympathetic to African independence, politically, and to Nkrumah personally. The US played a highly equivocal role in terms of supporting Nkrumah’s industrialization agenda, though. Washington tempered international support for the financing of the Akosombo Dam, which Nkrumah wanted to supply the cheap electricity he felt was needed to industrialize. And due to Cold War considerations, it also withheld final support for this project in the form of loan guarantees practically to the end of Nkrumah’s rule.

Victoria Brittain : Can you say something about the elimination of Lumumba and its impact on Nkrumah?

Howard French : Over the course of this project, I came to see Nkrumah’s strong and principled support for Lumumba as the lynchpin of his relationship with the West. Eisenhower’s national security team firmly believed, wrongly, that Lumumba was a communist, and Nkrumah’s use of political and economic capital to help Lumumba (sending some of the world’s first UN peacekeepers to Congo, speaking powerfully at the podium of the United Nations, and forging a political union with Congo) soured the American security state against Nkrumah both in an immediate and long-term sense. This carried over into the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Victoria Brittain : How do you feel about Nkrumah’s enduring legacy?

Howard French : I conclude the book by dealing with what I’d call some of the afterlives of Nkrumah, and there are many of them. One involves a modern stream of the return to Africa project, a dream that has animated Black people of the diaspora since the 19th century. I have brought in figures as diverse as Stokely Carmichael and Maya Angelou, and the experience of major intellectuals who lived in Ghana like David Levering Lewis. Another thread leads to Julius Nyerere, who had differences with Nkrumah but who admired him and learned a tremendous amount from Ghana’s example. In latter stages of his life, Nyerere embraced Nkrumah almost unreservedly as a hero. Finally, I speak of the much younger Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso who was a mere 8 years old when Ghana became independent. In some important respects, Sankara can be seen as a political descendant of Nkrumah’s, and I briefly recount getting to know him at the outset of his rule when I was a young journalist. In some respects, these were the most enjoyable parts of the book for me to write, and I hope that people will feel that as readers.