February 2025, Cibitoke, in north-west Burundi. In this provincial town with its ochre dirt streets, soaked by heavy rain at this time of year, Gabriel Nzosaba* has taken the time to tell his sister’s story. Saidata* had left for Saudi Arabia a year earlier, where a job as a housekeeper awaited her. She never saw Cibitoke again. Four months after her arrival, she died in circumstances that have yet to be explained. She was 24 years old. Her brother says that she regularly communicated with her family via various private messaging services. In February 2024, on her arrival, she sent a message in Kirundi: ‘Mie huyu’ (‘I am here’). According to her brother, the exchanges came to an abrupt halt after a final message was received on 8 June 2024.

Several corroborating testimonies have alloed the family to reconstruct part of the young woman’s life: Saidata had left her employer, with whom she no longer got on, before being picked up by some ‘Dalalas’. This Swahili slang term, widespread among Kenyan domestic workers, refers to ‘disreputable intermediaries’, according to an investigation by the French media outlet France 241. They promise foreign workers that they will find another employer, but often end up exploiting young women in vulnerable situations. According to our information, Saidata then lived in a house in Riyadh with other women. These houses of passage are also called ‘offices’. It was there that she fell ill.

Saidata’s family learned of her death via social networks. They were then put in touch with Joël Ndayisenga, the second counsellor at the Burundian embassy in Saudi Arabia. The family said that he directed them to the Burundian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to repatriate the body, although Ndayisenga denies that. According to the brother, this operation was to cost 17 million Burundi francs (BIF, around €5,000). This was a sum that the young woman’s family did not have. The minister, Albert Shingiro, finally convinced Saidata’s father to bury his daughter in Saudi Arabia with the help of Burundians living there. The family asked Joël Ndayisenga to send them photos of the funeral. He never did. The only consolation was that the parents were able to recover her personal affairs.

An initial alarming report from the United States

Saidata’s case is far from isolated. For several months, Burundian and international journalists from the investigative platform Ukweli, which specialises in the Great Lakes region, in partnership with Afrique XXI and Africa Uncensored, have been investigating this export of labour to Saudi Arabia.

According to the newspaper Jimbere, 65% of young people in Burundi have no formal employment2. With an average income of around monthly wages of 17 euros, the country is one of the poorest in the world. Under these conditions, the Saudi Eldorado sounds like paradise. But the abuses and violence described by the dozen or so witnesses who agreed to talk to us paint a picture of hell on earth. The ramifications of this trafficking, organised by Bujumbura under the cover of a bilateral contract signed with Riyadh, can be traced back to powerful Burundian men who reaped substantial profits without ever being questioned, despite their failure to comply with national regulations and the flagrant human rights violations. The state, recruitment agencies in Burundi and Saudi Arabia, crooked intermediaries... All are enriching themselves on the backs of these vulnerable workers.

In 2023 already, the situation of female Burundian emigrant workers, the behaviour of recruitment agencies and the State’s inability to protect its nationals were singled out in a US government report3 on human trafficking. ‘Observers noted the government’s failure to ensure that labour recruitment companies did not engage in trafficking,’ the document said.

An MP involved in violence

The report also points out that the government said that 676 Burundian women working in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait as domestic workers have received consular support, legal services and repatriation assistance between 2020 and 2022, some of whom are victims of trafficking. However, ‘international organisations have identified 1,409 potential victims of trafficking (...) among female migrant workers returning from abroad during the period under consideration [2022, editor’s note], compared with 1,380 in 2021’. Hundreds, if not thousands, of these workers have been left to fend for themselves — even though the government and its agencies have pocketed tens of millions of dollars, some of which were supposed to be used to help them.

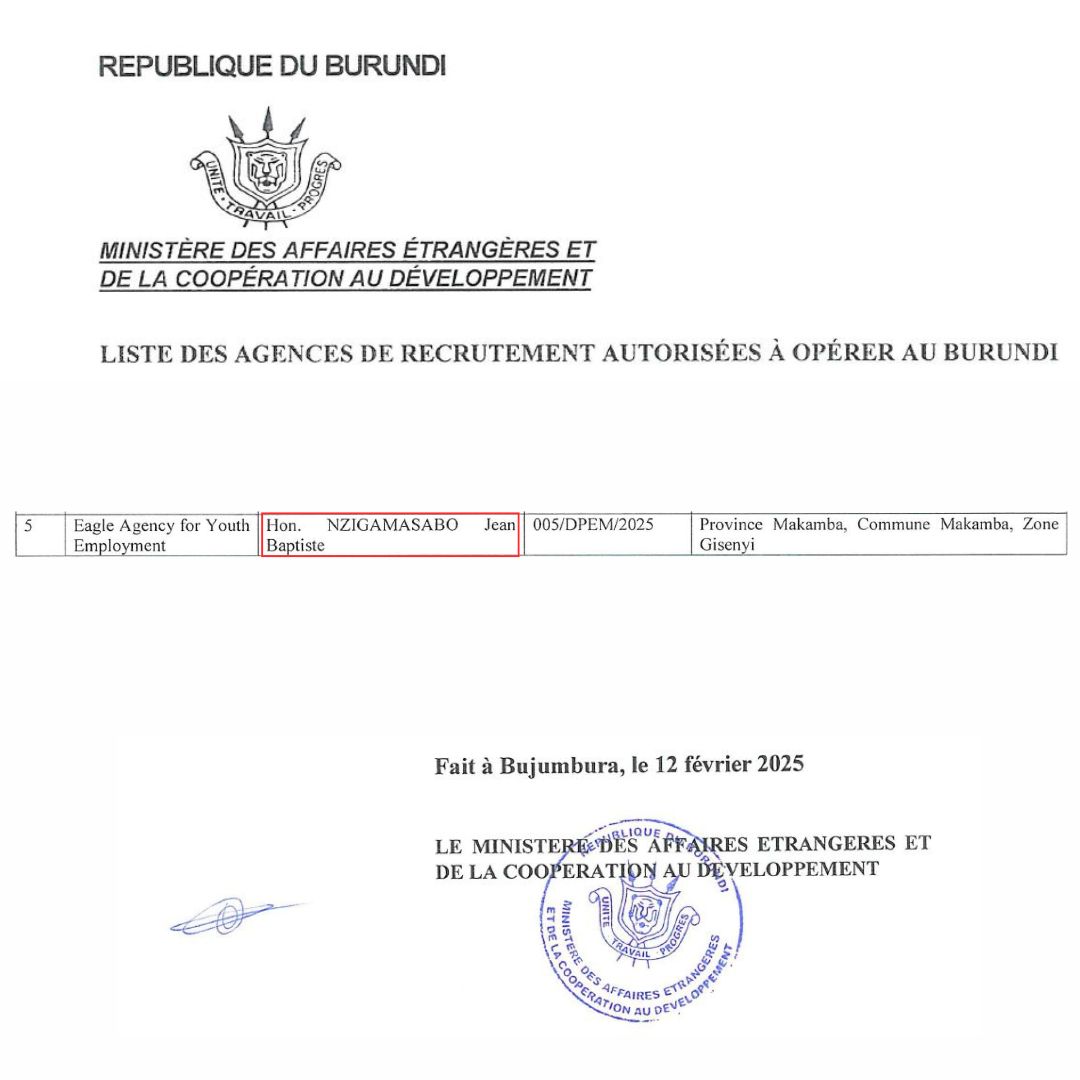

Many of them are afraid to speak out, like Marie*, who is currently working in Riyadh. She was sent by the Eagle Agency for Youth Employment. This company belongs to Jean-Baptiste Nzigamasabo, alias Gihahe, a member of parliament for the ruling party, the Conseil National pour la Défense de la Démocratie-Forces de Défense de la Démocratie (CNDD-FDD), which has just won 100 percent of the seats in the National Assembly following the communal legislative elections on 5 June.

On 20 February 2021, in its weekly report No. 2714, the ngo SOS Torture Burundi implicated the MP’s bodyguard in the murder of three teachers in Kabanga, in the north of the country, a week earlier, against a backdrop of political rivalry. Baptiste Nzigamasabo had already been named by Human Rights Watch5 in connection with pre-election violence in 2010. He was never convicted. After first agreeing to testify, Marie finally declined, saying that “it could become dangerous [for me and my family]”.

The recruitment and deployment of Burundian domestic workers to Saudi Arabia is supposed to be governed by an agreement signed between the two countries on 3 October 2021. It stipulates, among other things, that ‘the parties shall set up a mutually acceptable recruitment, deployment and repatriation system for Burundian domestic workers for employment in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in accordance with the laws, rules and regulations in force.’ In addition, the employment contract must be accepted by the competent authorities of both countries and must be respected by the contracting parties (employer, domestic worker, Saudi recruitment office and Burundian recruitment agency). It is also stipulated that the recruitment agencies in both countries and the employer shall not charge or deduct from the domestic worker’s salary any costs relating to his/her recruitment and deployment.

Workers accused of being “incapable”

Another clause stipulates that the government must ensure the well-being of female workers. The agreement also states that Saudi Arabia will facilitate the rapid settlement of disputes relating to the violation of employment contracts and other cases brought before the competent Saudi authorities or courts. For its part, the Burundian government must provide qualified and ‘medically fit’ domestic workers, in accordance with the requirements of the job specifications, and ensure that future domestic workers are trained in specialised institutes and given an introduction to Saudi customs and traditions. It must also ensure that the terms and conditions of the employment contract are fully understood by the candidate. In the event of a breach of the clauses, repatriation is theoretically the responsibility of Burundi.

Following the signing of this agreement, a large number of labour recruitment agencies were set up. There are currently twenty-seven of them, of which twenty-six are located in Bujumbura and one in Makamba in the south (owned by MP Gihahe). In February, during the presentation of the achievements6 of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, minister Albert Shingiro announced that the total number of Burundian women working in Saudi Arabia, before and after the agreement, had reached 17,000. This contract between the two countries was supposed to provide better protection for workers who emigrated 5,000 kilometres from their homes to a country whose customs and traditions are radically different from their own. But the reality is quite different.

At an open day organised at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 7 May 2024, Mertus Ndikumana, president of the Association of Private Recruitment Agencies of Burundi (Oraab), said that around a hundred workers sent to Saudi Arabia had returned, dissatisfied with their work7. However, according to a source in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who wished to remain anonymous, more than 500 workers have in fact returned home in a hurry since the agreement was signed. This source reported that the Burundian recruitment agencies accused these workers of being “incapable” of carrying out their duties.

“Serious injuries” and “psychological consequences”

This version is contradicted by Eddy Manirakiza, project manager at the Fédération des Associations Engagées dans le Domaine de l’Enfance au Burundi (Fenadeb), an organisation that has also been dealing with human trafficking for several years. “Between October 2023 and January 2025, we received 66 presumed victims of human trafficking,” he explains. “37 were girls who had returned from Saudi Arabia, 8 from Oman, 3 from Kuwait and 3 from Kenya.” According to Eddy Manirakiza, “of the 66 cases identified, all had been subjected to several of the forms of violence that characterise human trafficking, such as the use of force, coercion, intimidation or threats”. He points out that “some suffered serious injuries, while others bear the psychological scars of their experience”.

Amina*, a woman in her forties, returned from Saudi Arabia in November 2024 due to health problems. She is now suffering from spinal shock, the result of physical violence inflicted by her employer. “My boss was extremely cruel. She always found excuses to hit me. I regret having taken the decision to leave without first seeking advice”, she says.

Eddy Manirakiza adds that recruitment agencies in Burundi do not monitor the women they have sent abroad, even when they return. What’s more, these women, the vast majority of whom “live in extremely precarious conditions in Burundi”, do not dare to lodge complaints, as they are often unaware of the terms of their contracts with their employers, attracted above all by the prospect of improving their situation and that of their families. For Mertus Ndikumana, President of the Association of Recruitment Agencies mentioned above, these companies respect the law: “If a woman has a problem, it is the duty of the agency that sent her to assist her.”

A former leader of the Imbonerakure militia turned recruiter

An agency employee who agreed to testify on condition of anonymity offers a different version. We’ll call him Pascal. In practice, he explains, “there are times when the worker is obliged to pay her return ticket herself”. He continues: “If she is unable to do so, the agency that recruited her or the Burundian embassy in Saudi Arabia pays for the ticket. But in this case, it’s a long process and the girls can go months without assistance.” Another agency employee explains that “when a worker wants to return before two or three years have passed because she is unable to do her job, it’s a big loss for the agency, which reimburses the Saudi partner agency more than $1,800”. She added: “There are times when the migrant worker is imprisoned until she pays the airfare.”

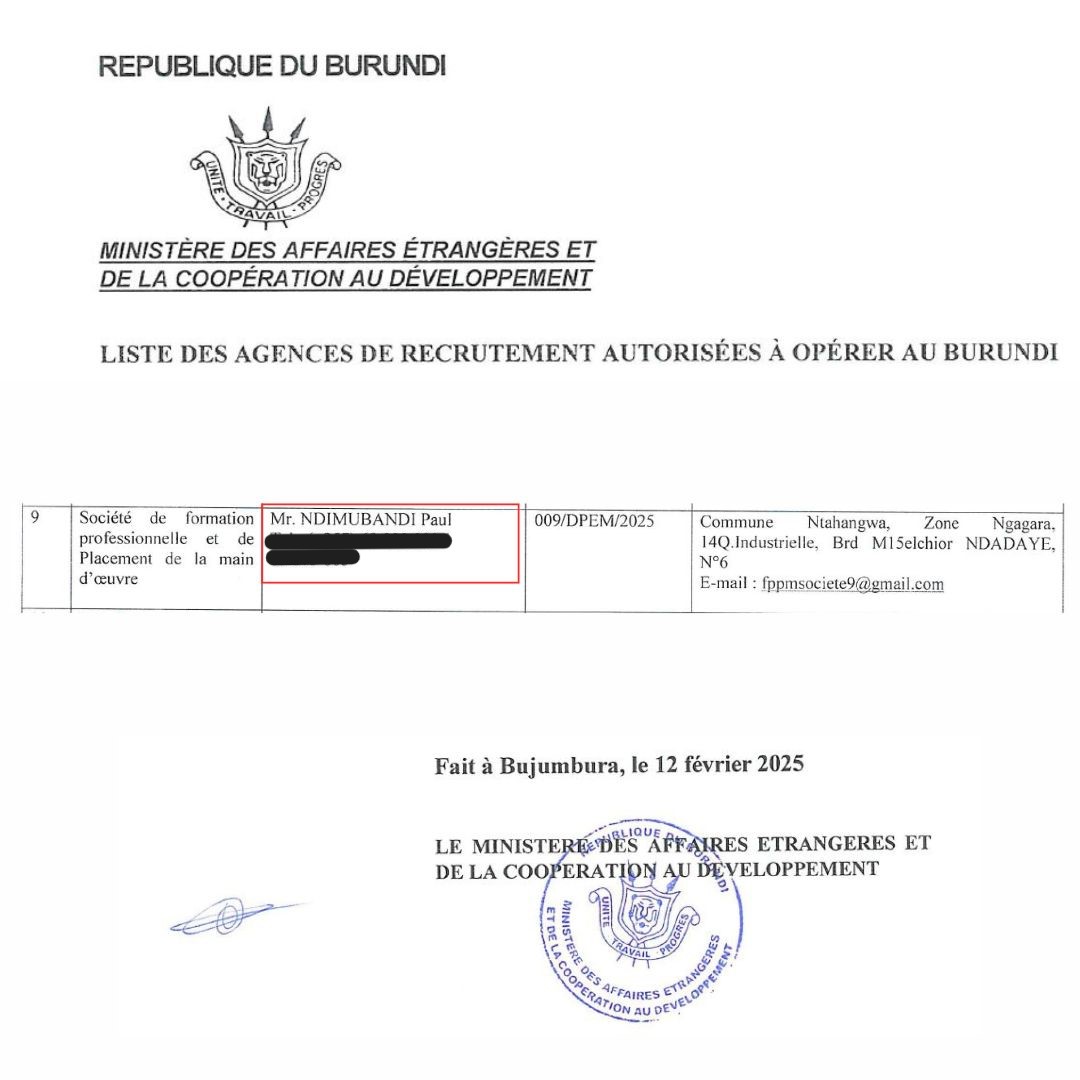

Bahati* is 28 years old and comes from a province in the north of the country. In 2023, a woman from Bujumbura came to her commune to recruit “girls” with passports who wanted to work in Arab countries. This intermediary put her in touch with the Société de Formation Professionnelle et de Placement de la Main d’œuvre (SFPPM). According to the official list of state-approved recruitment agencies that Ukweli was able to consult, and according to information cross-checked by Ukweli, this Bujumbura-based company belongs to Paul Ndimubandi, the former Secretary General of the ruling party’s Youth League. Also known as Imbonerakure, this organisation is regularly accused of being a militia used for political repression8. When contacted, the SFPPM did not respond to our questions.

On 15 May 2023, after a brief training course in housekeeping, Bahati flew to Saudi Arabia from Melchior Ndadaye airport. The very next morning, she took up her post under the orders of her new boss, who had made sure to confiscate her passport. Two months after she was hired, Bahati fell ill and her ordeal began. While doing domestic work, she became dizzy, fell to the floor and lost her sight. Her boss tried to get her treated before taking her back to ‘the office’, a liaison centre where immigrant workers are gathered when they arrive or are awaiting repatriation. “I spent seven long months locked up, sick and malnourished. During all that time, I wasn’t treated”, Bahati confides. A long struggle for her return to Burundi began. According to Bahati, Jacques Ya’coub Nahayo, Burundi’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, even called Jean-Paul Ndimubandi, the head of the SFPPM. On 12 January 2024, Bahati finally landed in Bujumbura. Jean-Paul Ndimubandi has not responded to our requests, while Jacques Ya’coub Nahayo redirected us to the ministry of foreign affairs (see box).

“A Kenyan woman committed suicide out of desperation”

Several other young women described extremely harsh living conditions in these offices. One of them recalls, still shocked:

In the morning, we were given bread and tea. In the evening, they brought us rice and cabbage to cook. But sometimes we’d go two or three days without supplies, and therefore without eating. Sometimes we had to bang on the door to get food. One Kenyan woman even committed suicide out of desperation.

When she returned, Bahati was taken in by her family for treatment. In all, she received 700 Riyals (162 euros) for one month’s work, the salary she was told she would be paid before she left and the only detail of her contract that she knew. She was never given a copy of her contract. Since her return, she has heard nothing more about the SFPPM. In 2023, Jean Bosco Bizuru, one of the SFPPM’s agents, stated that he would ensure that the “rights [of those recruited] were respected”.

According to Bahati, she spent seven months locked up in this office because neither of the two recruitment agencies, Saudi or Burundian, was willing to pay for her plane ticket. Other women interviewed as part of this investigation have described similar experiences.

In a response to senators9, following the signing of the bilateral agreement in October 2021, Foreign Affairs Minister Albert Shingiro reassured that “(...) [the] international conventions and [the] national laws of many countries require that all costs related to the recruitment of migrant workers be paid by their employers. To this end, regulating and controlling recruitment costs means taking measures to prohibit the charging of recruitment and related fees to workers and jobseekers.”

Medical examination and bribe paid by recruited worker

In April 2022, during the examination10 of the bill to validate the agreement between Burundi and Saudi Arabia, the then Minister of the Interior, Gervais Ndirakobuca, indicated that the contract should make it possible to “put an end to speculation by bogus commission agents who were asking for application and travel fees [from recruits] when these were being paid by their employers". Not everyone was convinced by these speeches. Euphrasie Mutezinka, a member of parliament from the opposition National Congress for Freedom party, points out that many elected representatives did not vote in favour of the bill, precisely because of the loopholes in the protection of workers. In her view, “if female workers are mistreated, the recruitment agencies should be held responsible.”

Does this ‘El Dorado’ at least pay off for the workers? Contracts are for a renewable period of two years. The agency employee quoted above explains that “the salary depends on the Saudi agency that submitted the offer. It is generally between 800 and 900 Riyals (185 to 209 euros). For those who have already worked in countries such as Iran, Kuwait, Jordan or Oman, their salary varies between 1,000 Riyals and 1,200 Riyals.”

Cynthia* has been in Saudi Arabia for five months. “As an orphan, it was a godsend for me to be able to earn money abroad and provide for my brothers and sisters. I didn’t hesitate for a second.” The 22-year-old says she currently earns 800 Riyal a month (185 euro). Francine*, 35, married with two children, left in June 2024. She earns the same salary as her compatriot. However, she feels that this is not enough.

Above all, contrary to the Burundian government’s announcements, the two women claim to have spent a lot of money to leave. “The passport, criminal record extract, medical examinations, visa and training fees cost me more than BIF 1 million (290 euro),” says Cynthia. The agency only paid for the plane ticket. In addition to these charges, Francine says she had to pay a bribe: “I paid around 2 million BIF to an agency employee to get on the list.”

When asked how much the Saudi agencies pay their Burundian counterparts for each recruit, Pascal, our anonymous employee interviewed above, demurs: “That’s a professional secret”. Interviewed11 in April 2023, Ramadan Mugabo, Director of Operations at the recruitment agency Al-Harmain recrutement LTD, confided that each worker sent earned him “1,400 dollars” (1,211 euros). According to him, this sum is insufficient to cover all the costs, including the cost of the plane ticket, care during training, bank charges and so on. He continues: “After all the expenses, the agency is left with a maximum of 30 dollars per person recruited. But if we recruit a lot of workers, we can earn a lot.”

Tens of millions of dollars earned

Another former employee of a recruitment agency agreed to speak out a bit more. The Saudi agencies paid the Burundian agencies between 1,500 and 2,000 dollars per recruit. At this rate, Burundian companies would have earned between $25.5 million and $34 million for the 17,000 female workers sent to Saudi Arabia as announced by the Minister of Foreign Affairs. “The agencies are making a lot of money at the expense of these workers. That’s why these companies hide the contracts they sign with their counterparts in Saudi Arabia”, Pascal concedes when confronted with these figures.

The investigation also uncovered a few details about the employment agencies in Saudi Arabia, which are also making money off Burundian workers. The Safwat Al-Nokhba agency, for example, charges 13,400 Riyals (3,100 euro) per worker placed. Makin charges 10,400 Riyals, while Mithaq Al-Madine charges its clients 12,000 Riyals.

The Burundian government is not to be outdone. In a memo12 dated 8 August 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Development Cooperation details the criteria for awarding a recruitment agency licence. The agency must pay a deposit of 50 million BIF to the Bank of the Republic of Burundi (BRB), ‘which will serve as compensation for the damage suffered by the Burundian migrant worker’. If the application is approved, the recruitment agency must pay 100 million BIF into the public treasury account opened at the BRB. The licence certificate is valid for two years, renewable on further payment of 50 million BIF.

And that’s not all. Before the departure of each migrant worker abroad, an identification form is collected by the agency from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This form is obtained after submission of a dossier consisting of an extract from the criminal record, the employment contract, the visa, the plane ticket, a medical document and a payment slip for 100,000 BIF. In his aforementioned statement of achievements presented in February, Albert Shingiro proudly announced: “Burundi has already collected just over 10 million dollars and 10 billion BIF. Saudi Arabia has accepted [to welcome] 75,000 migrant workers over the next five years.” A sum that could have enabled Saidata to see her village again, rather than end up buried alone in the sands of her lost El Dorado.

*First names and surnames have been changed.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism:

1Audrey Travère, “Arabie saoudite : les “dalalas”, intermédiaires douteux qui prétendent sauver les domestiques africaines”, France 24, 24 February 2023, read here.

2The Jimbere newspaper (article here) is approved by the national media regulator, but the International Labour Organisation, which uses statistics supplied by states, gives a much lower figure: according to it, 12.6% of young people aged 15-24 are neither in employment, education or training.

3The “2023 Trafficking in Persons Report: Burundi” is available here.

4All the reports are available here.

5Human Rights Watch, “Burundi: Authorities should end pre-election violence and hold perpetrators to account”, 14 April 2010, read here.

6Claude Hakizimana, “Ministère en charge des affaires étrangères : Présentation des réalisations du premier semestre 2024-2025”, Le Renouveau du Burundi, 4 February 2025. Read it here.

7Jules Bercy Igiraneza, Engager la diplomatie économique pour baisser le chômage à travers des travailleurs migrants, Iwacu Burundi, 10 May 2024. Read it here.

9Sénat de la République du Burundi, “Rapport d’analyse par la Commission permanente chargée des questions sociales, de la jeunesse, des sports et de la culture du projet de loi portant ratification par la République du Burundi de l’accord sur le recrutement des travailleurs domestiques entre le gouvernement de la République du Burundi et le gouvernement du Royaume d’Arabie saoudite”, 4 May 2022, available here.

10Cellule Communication, presse et porte-parolat de l’Assemblée nationale, Analyse et adoption de deux projets de loi de ratification, 22 April 2022, read here.