The war in eastern DRC overshadowed the most recent Francophonie summit held in Villers-Cotterets, France, in early October 2024, prompting Felix Tshisekedi to cut his visit short. The Congolese president was irked by the French president, Emmanuel Macron’s opening speech, which omitted any mention of the crisis in North Kivu, and by his warm welcome reception of Paul Kagame his Rwandan counterpart, who is suspected of supporting an armed group in the region. But behind these diplomatic scuffles, and despite the grim situation on the ground, foundations are quietly progressing in the region. The DRC’s neighbours are increasingly alarmed by this war, which threatens Central Africa’s stability and stalls potential economic developments.

This concern motivates Angolan President João Lourenço, the appointed mediator in the so-called “Luanda Process”, to persist tirelessly in his peace efforts. While Kinshasa opts for military solutions despite setbacks, Angola continues to advocate for a political resolution. On August 4, 2024, Lourenço secured a ceasefire agreement between Kinshasa and Kigali. However, clashes persist, with the M23 rebel movement, backed by Kigali, recently capturing the strategic town of Kalembe from poorly equipped government forces.

The equation remains unchanged: Kinshasa accuses Rwanda of supporting the M23, a group of Congolese Tutsis who claim to be discriminated against. Biannual reports by UN experts regularly and thoroughly document Rwanda’s support for the group. Kigali, however, consistently denies these allegations, accusing the Congolese army of collaborating with longstanding adversaries, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) was originally made up of soldiers and militiamen involved in the 1994 Tutsi genocide, whose descendants allegedly continue to share their ideology. Broadly speaking, Kinshasa accuses Rwanda of siphoning off the mineral wealth of eastern Congo, including the Rubaya mine in North Kivu, one of the world’s largest cobalt reserves.

From the DRC to the United States

Lourenço’s determination to mediate is not solely driven by African solidarity or neighbourly goodwill. Angola enjoys the backing of the United States and the European Union (EU), which aim to fast-track a significant regional economic cooperation project known as the “Lobito Corridor.”

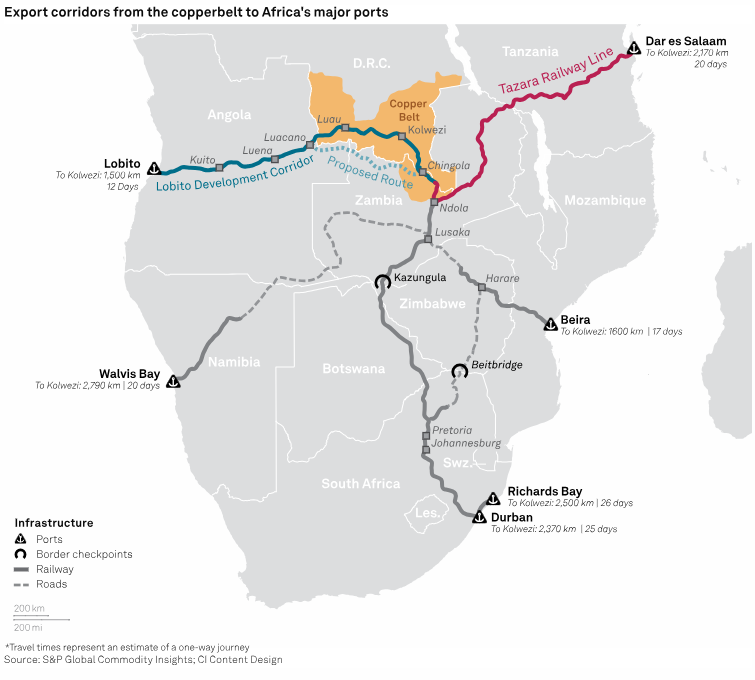

This initiative would connect southern DRC and northwestern Zambia to Angola’s Atlantic Port of Lobito through a 1,300-kilometre railway. This route would enable the export of mineral resources from Katanga to the west rather than exclusively relying on Indian Ocean ports.

This strategic economic project was revitalised in May 2023 as part of the G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment and later at the “Global Gateway” forum in October 2023. The EU and the United States signed a memorandum of understanding with Angola, the DRC, Zambia, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the Africa Finance Corporation to outline the objectives of this corridor. The goal is less about opening up the continent’s mining heartland and more about redirecting its resources towards the Atlantic and US ports.

An old colonial project

In Brussels, former colonial stakeholders emphasise that this idea is nothing new. Before DRC’s independence in 1960, Belgians in Katanga often used this route, either by road or through the Benguela Railway, to reach Angola’s Atlantic coast. Much of the Union Miniere du Haut Katanga’s copper and uranium production followed the same path, with uranium ultimately reaching the United States.

The wars following Angola’s independence in 1975 and lasting through the Cold War rendered the railway inoperative. On the Congolese side, poor maintenance and a shift to road transport completed its obsolescence, despite its lower cost and environmental impact.

Bilateral agreements between Kinshasa and Luanda in recent years have sought to rehabilitate the railway. Angola has rebuilt its section, constructing 30 stations, developing double tracks, establishing an international airport in Lobito, and adding a mineral and oil terminal along with a dry port for goods. China is not absent from Angolan development and plans to build a refinery in Lobito. However, on the Congolese side, the remaining 427 kilometres remain a bottleneck. The railway, built between 1902 and 1929, still awaits restoration.

China’s monopoly

Joseph Kabila, in power for 18 years and disillusioned with Europe’s lack of interest in the early 2000s, turned to China in 2006, endorsing “win-win” partnership that exchanged access to minerals for infrastructure projects, known as the “five major projects”.

Even today, Chinese companies dominate Kolwezi, the mining hub. Vast slag heaps overshadow this colonial – era town, where artisanal miners dig trenches under houses and businesses. Truck convoys transport minerals-often unprocessed and barely sorted-to Indian Ocean ports like Durban, South Africa. The pollution from these routes poisons villages along the way.

Copper, uranium, cobalt and other strategic minerals from the Congolese and Zambian Copper Belt are at the heart of China’s near monopoly in digital technology. Instead of a thriving “Silk Road”, dusty trails across African savannahs supply Chinese factories producing tech equipment. During his first term (2018–2023), Felix Tshisekedi was heavily courted by Western powers eager for a political shift in their favour.

Joe Biden’s missed appointment in Angola

To counter China’s commercial and technological dominance, the US and EU have prioritised the Lobito Corridor. Advocates claim the route could slash transport times, enabling goods to reach the Atlantic in eight days instead of a month to Indian Ocean ports. This “express route” aims to unlock the region’s vast economic potential while enhancing Angola, DRG and Zambia’s exports.

Goods shipped from Lobito would head to the Atlantic’s opposite shore, where American companies are keen to challenge Chinese competitors. This ambition prompted President Joe Biden to consider visiting Angola – a trip that would have been his only one to Africa-before he decided against seeking a second term. It also explains why Washington and Brussels support João Lourenço’s mediation efforts.

China’s response to this Western challenge remains to be seen. During the China – Africa Cooperation Forum (September 4-6 2024) Tshisekedi received a warm welcome – unlike his reception in Paris days later. Chinese officials reaffirmed their commitment to the DRC’s territorial integrity. However, Tshisekedi, having campaigned on nationalism and promising a military victory by the end of 2023 in eastern DRC, now faces scrutiny from the public and is reluctant to negotiate with Rwanda-backed rebels. Moreover, DRC aims to reduce reliance on neighbouring countries’ ports, including allies.

Plans for a deep-water port in Banana, Bas – Congo, are moving slowly, while a newly inaugurated international airport in Mbuyi-Mayi aims to connect the region with the rest of the world. Recent surveys commissioned by Miba (Société Minière de Bakwanga) have uncovered significant nickel-chrome deposits, potentially revitalising the former diamond-rich Kasaï region. Miba’s CEO, Jean – Charles Okoto, plans to visit China following stops in Brussels and London. Amid this international rivalry, the “Luanda Process” for peace in eastern DRC remains stalled and the Lobito Corridor is far from operational.

If you believe in the importance of open and independent journalism :